Everyone is a product of their experience. My own experience was the original reason I believed strongly in microcredit. Personally, lending helped me get out of poverty— my parents' efforts to finance my education and scholarship programmes enabled me to enter higher education, allowing me to start my career at Morgan Stanley.

Unlike in the natural sciences, causal relationships in society are not crystal clear. Once you develop a certain perspective, you tend to see things through its lens. My overconfidence in microcredit had remained largely unaltered even after seeing the results of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on the impact of microcredit. My initial argument against the RCT results on microcredit was that if an MFI carefully selected its clients, microcredit could still bring about a significant impact.

What eventually changed my view of microcredit was a series of field studies I conducted. I borrowed from the research methodology of Stuart Rutherford, one of our Directors and a renowned microfinance practitioner. The research focused on understanding how people manage their money.

Here is how the research would go: I would randomly visit households in an area where financial service providers operate. Then I would explain to the villagers that I was conducting research on the economy of the township. (I don't like to lie, but couldn’t say that I was from a microfinance organisation, in case it distorted people's answers.)

Then I’d ask questions in the following order. The order of the questions mattered, as if I had asked the questions about finance first, I would have been less likely to get answers that closely reflected the reality of their lives.

- Household: family members, native town, age, education, etc.

- Occupations: type of businesses/jobs, unit economics, etc.

- Assets: house, land, vehicles, etc.

- Finances: ask how they deal with the excess or shortfall of the cash

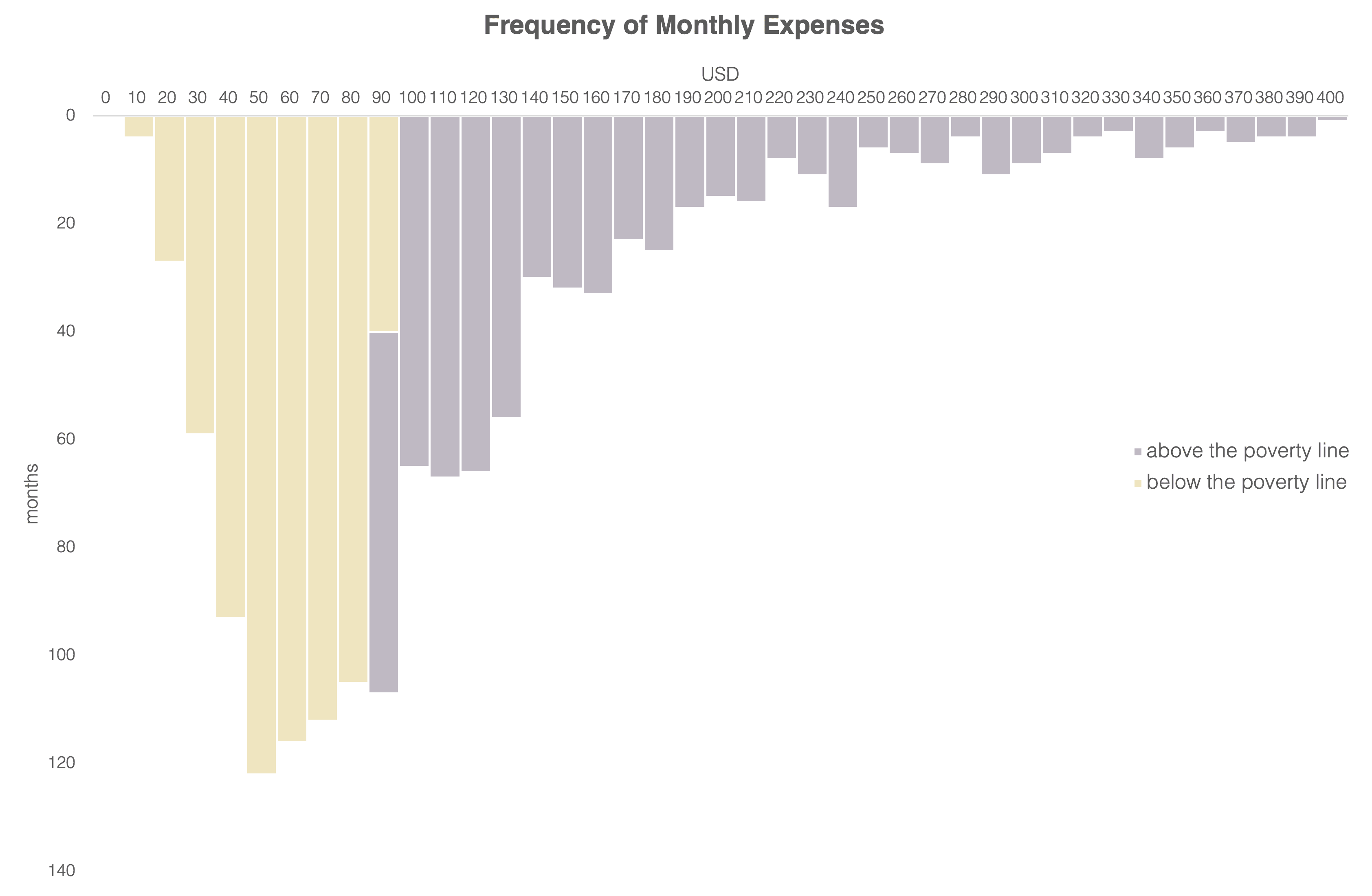

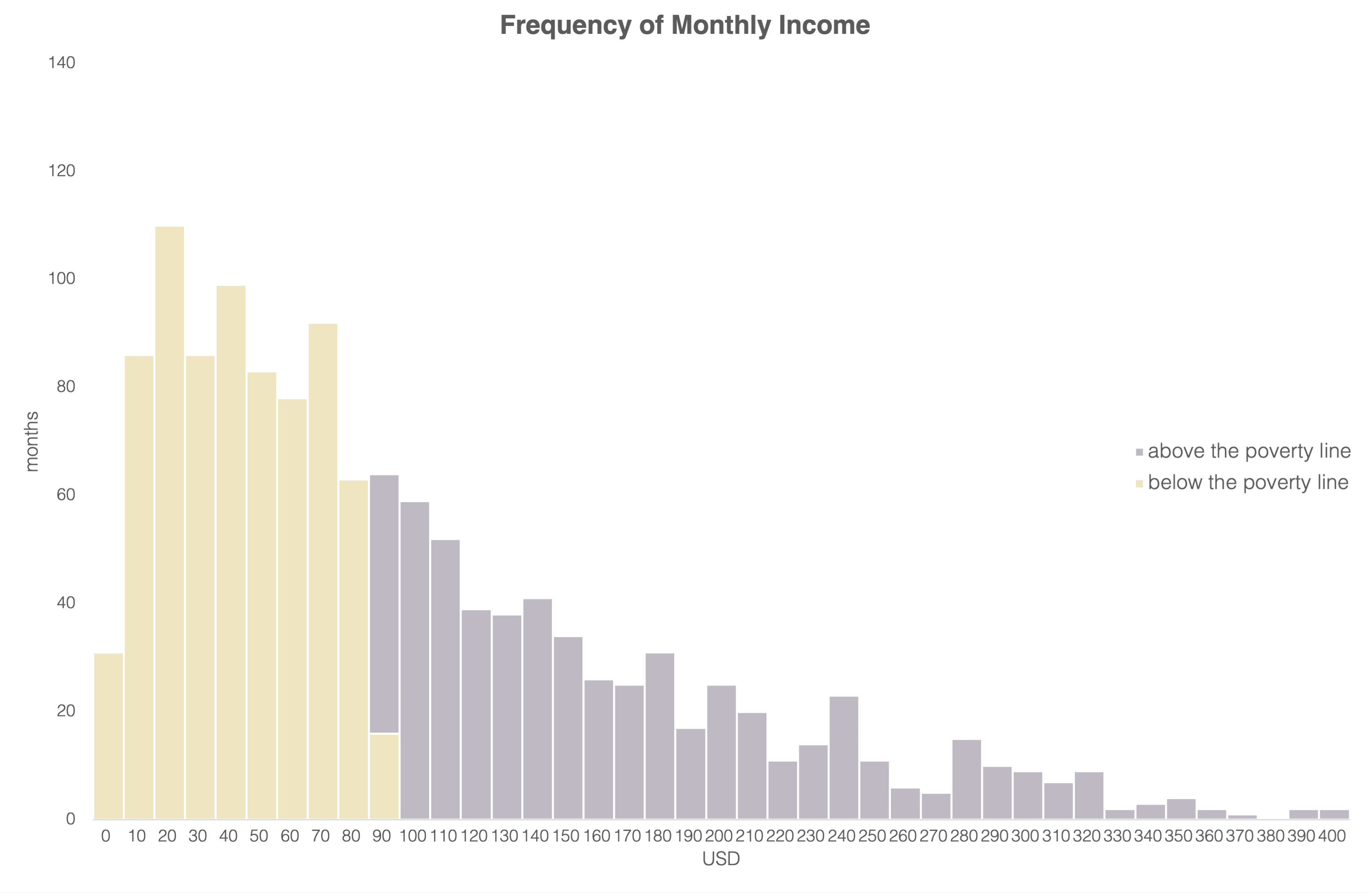

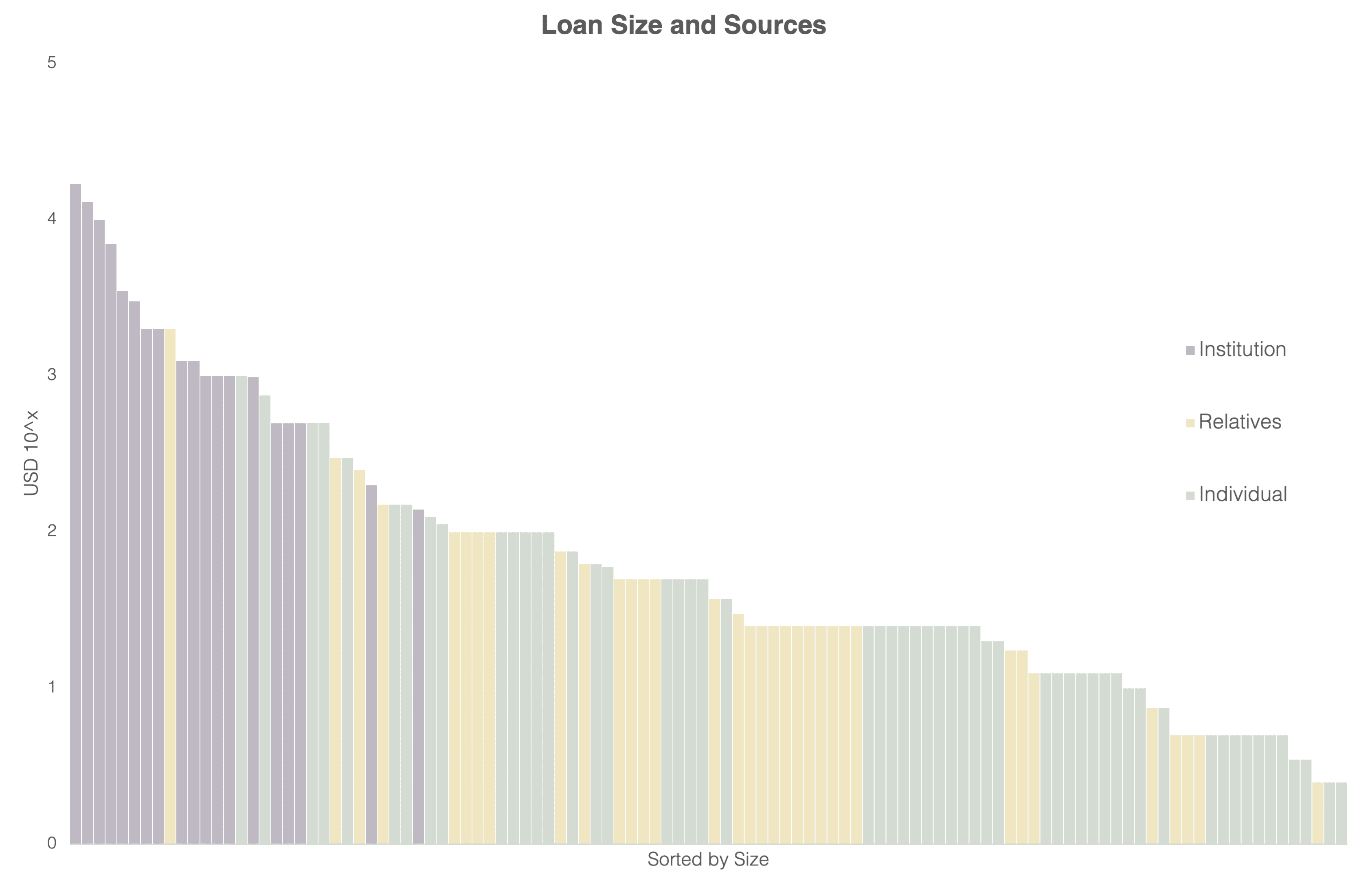

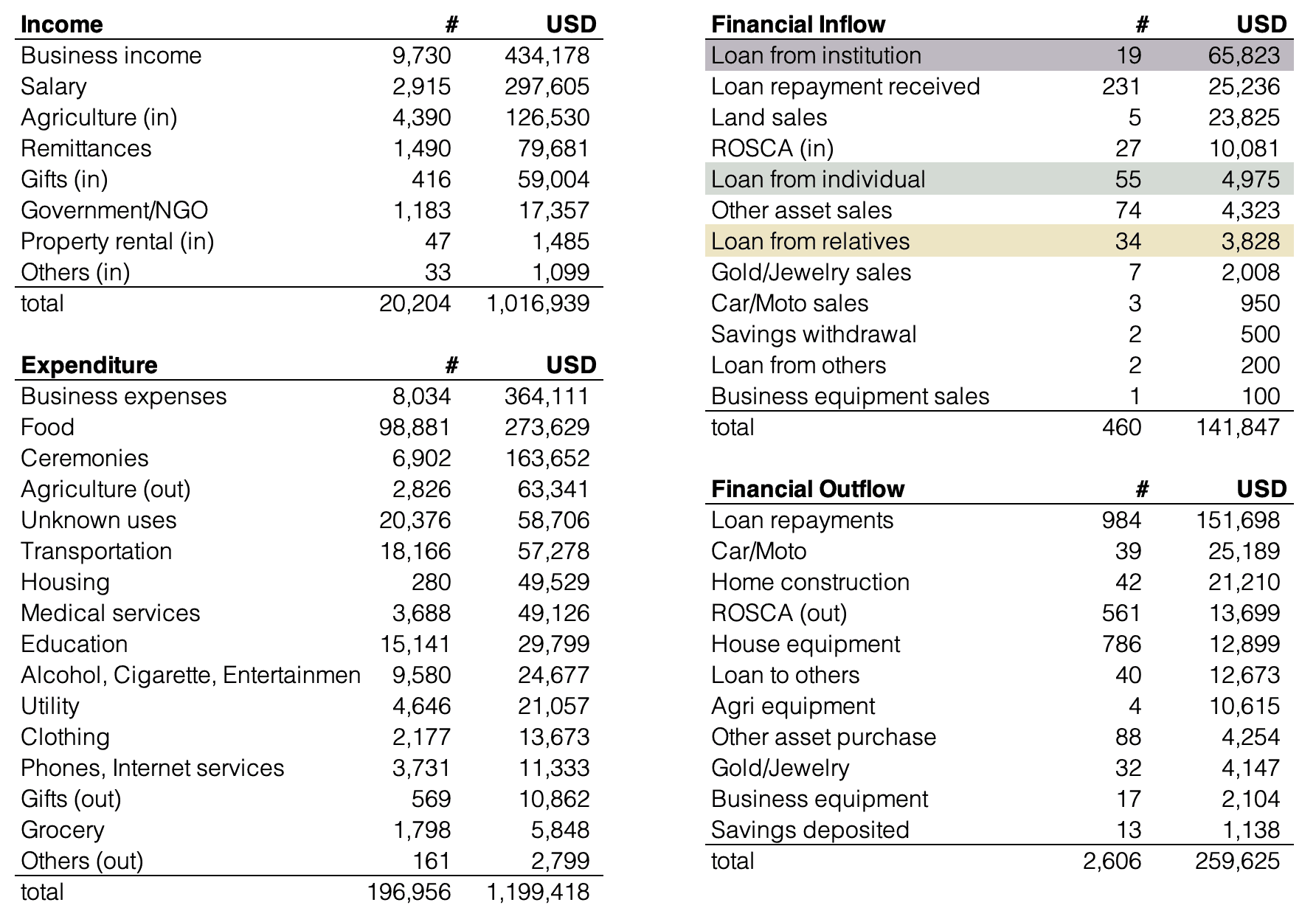

The sample size was not large, but the results were strong enough to make me revisit the impact of microcredit. Somehow, the people who were borrowing loans from MFIs were less affluent (at least in terms of liquidity) than those who didn't. For example, those who had microcredit tended to have more assets, but were facing difficulty in managing their monthly cash flows, including repayments to MFIs. On the other hand, those without microcredit didn’t own many assets (and thus at face value seemed to be less affluent), but they could easily achieve positive net cash flow every month and often added to their reserves for a rainy day.

On top of this, the MFIs the villagers mentioned were reputable ones in the country. I needed to face the facts sincerely.

There are two things that could have explained this. First, it could have been that the microcredit interest rate was higher than the average return on investment of the customers. Second, it could have been that MFIs provided loans to unpromising businesses.

The first didn’t sound plausible, because there are many good investment opportunities that can generate 100+% return on investment. For example, if you buy 100 chickens for $500, then you can generate $3000 revenue per year. After subtracting personnel costs ($1-2 per hour) and cages and feeds ($200 or so), you still have $1,000 net income.

I became convinced that the second reason was the culprit. This is in line with the paper published by Duflo et al., titled “Can Microfinance Unlock a Poverty Trap for Some Entrepreneurs? (2019)”. Their study suggests that if microcredit is provided to those who ran the business before the funding, it does increase the income of the borrowers.

It made sense. Business loans are meant to expand businesses, not to start entirely new ones. Most entrepreneurs around the world create their companies with their own money, and after proving the concept, they begin borrowing money to expand their businesses further. Microcredit cannot be an exception. As many other successful business owners have done, people need to test their original business hypotheses with their own reserves and scale it to a certain level before obtaining loans, despite the difficulties they might face in building initial lump sums.

The experience made me think hard about how we can promote savings as a tool to improve clients’ outcomes, as well as a tool to leverage the impact of microcredit. Savings are not only a reserve by which people can survive rainy days, but also serve as seed capital by which people can improve their lives.

The challenge we are now working to solve at Gojo is how to provide useful and affordable saving services for those who don’t have smartphones, are not connected to 3G networks, are less literate, particularly in terms of digital services, and who live far away from microfinance branches. At Gojo these days, we are exploring various solutions and would love to hear from anyone with expertise in this area.

Taejun is the co-founder and CEO of Gojo. He is passionate about equality of opportunity. Prior to founding Gojo, Taejun worked in investment banking and founded Living in Peace, an NGO.