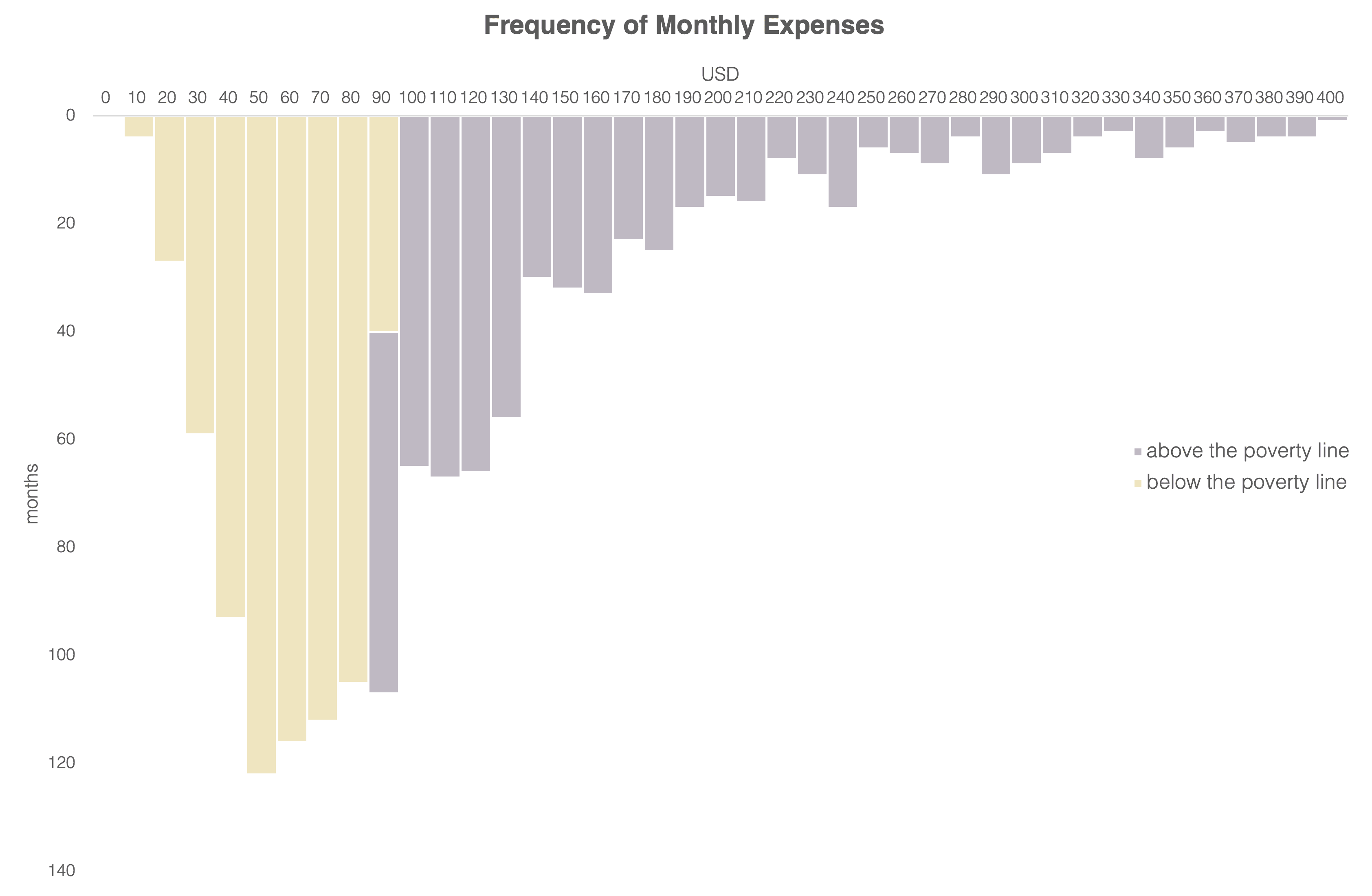

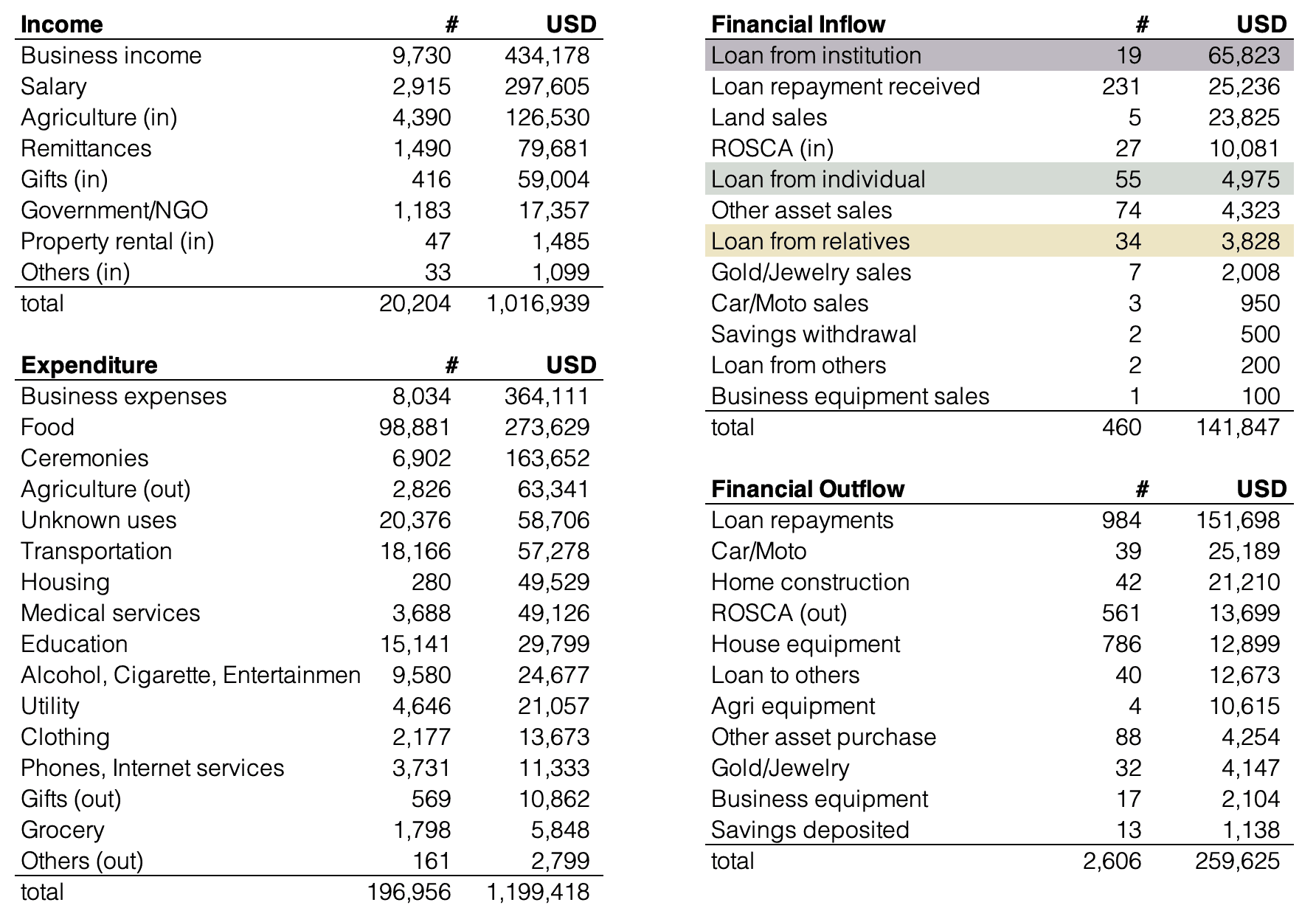

五常・アンド・カンパニー株式会社(代表執行役CEO:慎泰俊、本社:東京都渋谷区、以下、「五常」)は、金融、社会、経済的な包摂を推進するグローバル・コンサルティングファームであるMicroSave Consulting(以下、「MSC」) とHrishipara Daily Diaries Projectに関する協業を開始いたします。本プロジェクトは、フィナンシャル・ダイアリーの手法を用いて、バングラデシュ中部に暮らす低所得世帯の日々の金銭取引を記録し、家計や経済活動の実態を詳細に理解することを目的とした研究プロジェクトです。2015年にStuart Rutherford氏が開始し、五常は2024年7月に参画しました。

MSCとの協業は、プロジェクトの財務および技術面の強化を目的としています。MSCは、金融包摂分野における調査・データ分析・知見の発信に関する豊富な経験を有しており、これまで世界各地で多数のフィナンシャル・ダイアリー調査や応用研究プロジェクトを主導・支援してきました。本協業を通じて、ダイアリー・データのより深い分析を行い、投資家、実務家、政策立案者を含む金融包摂分野の幅広いステークホルダーに向けて、知見をより広く共有していくことを目指します。

MSC Bangladesh Country Director Zaki Haider氏コメント

Hrishipara Daily Diaries Projectにおいて五常とパートナーシップを結べることを大変嬉しく思います。本協業を通じて、長期的に蓄積されてきた人々の生活に関する深い洞察と、最先端のデジタル技術とをつなぐ架け橋を築いていきます。AIやデータサイエンスにおける私たちの専門性を活かし、低所得コミュニティ固有のニーズに即した実践的なAIソリューションの実証に取り組んでいきます。本プロジェクトを通じて、グローバル・サウスにおけるより包摂的で柔軟性のある金融商品・サービスの設計に貢献することを期待しています。

五常 Head of Impact Cheriel Neo氏コメント

Hrishipara Daily Diaries Projectに、低所得世帯の日々の暮らしの研究という志を共有するパートナーを迎えることができたことを喜ばしく思います。本協業を通じて得られる金融包摂に関する知見を、より広く発信していけることを楽しみにしています。

MicroSave Consultingについて

MSCは、27年にわたり金融、社会、経済的な包摂を推進してきたグローバル・コンサルティングファームです。400人以上の多様な国籍と専門知識を持つ社員が、70カ国以上で事業を展開しています。金融サービス、企業、農業、医療分野を中心とするエコシステムにおいて、政府、ドナー、民間企業、現地企業など幅広いステークホルダーと協働し、持続可能な事業および価値の創出を支援しています。また、デジタル分野における高い専門性を活かし、顧客の事業が将来にわたって変化に対応できるよう支援しています。

五常・アンド・カンパニーについて

五常は南アジア、東南アジア、中央アジア及びコーカサスの7カ国のグループ会社及び主な投資先を通じ、途上国においてマイクロファイナンスを展開するホールディングカンパニーです。金融包摂を世界中に届けることをミッションとして、2014年7月に設立されました。2025年3月末時点でグループ会社及び主な投資先合算の顧客数は約340万人です。2025年1月に「B Corp™」認証を取得し、社会的・環境的パフォーマンスの向上に取り組んでいます。