If we look back at the history of accounting, it has been changing and improving constantly since its birth, and the scope it is covering is spreading and adapting with the ever-changing world of business.

If we look back at the history of accounting, it has been changing and improving constantly since its birth, and the scope it is covering is spreading and adapting with the ever-changing world of business.

In this blog post we introduce The Fit Factor: Matching Loans and Savings to Cash Flows, a new paper from Gojo’s R&D team.

Typically, when we set out to measure the impact of a loan on someone’s life, we tend to look at what happens after they take the loan— for instance, whether their income increases, whether they are able to spend more on education, or whether they acquire more assets. However, there are a couple of limitations to this approach:

- Outcomes data taken following a loan tends to be a snapshot of a certain point in time, and is usually collected at a time pre-determined by the service provider, rather than at a time that makes sense for the borrower in terms of when they expect to see results from the loan

- Changes in income and increased spending on education can be influenced by many different factors in a person’s life, not just their access to finance. For instance, we see in financial diary research that unexpected events happen more often than we might think, such as accidents, sudden medical needs, new opportunities, and other events which may disrupt the original plans a borrower had for their loan

While outcomes data is useful, it cannot give us the full picture of the utility provided by a loan or other financial service. What if, in addition to outcomes data, we considered the impact of a financial service from a cash flow perspective? In other words, what if we could see how loans or savings fit with clients’ real cash flows and affect their day-to-day money management?

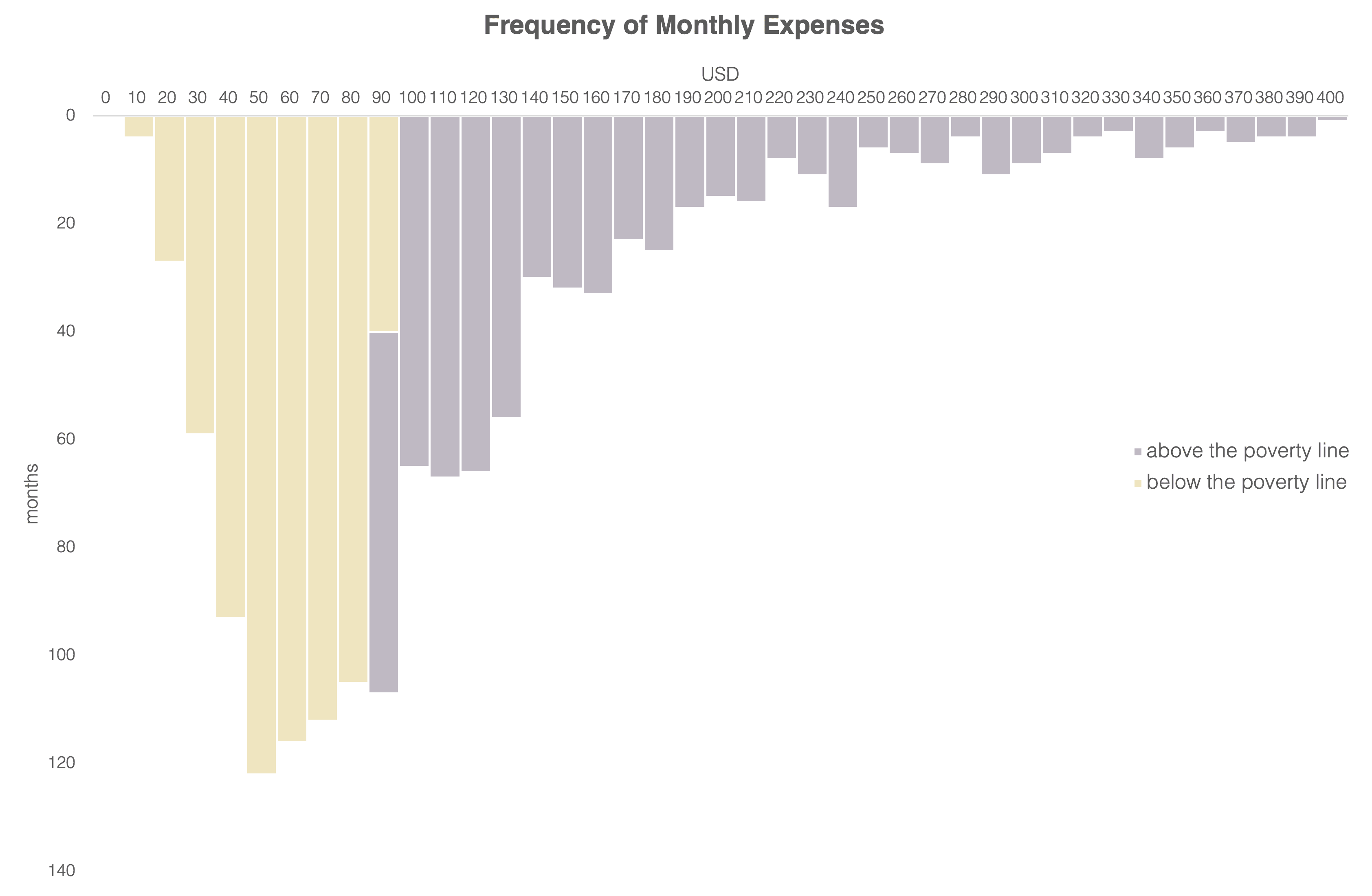

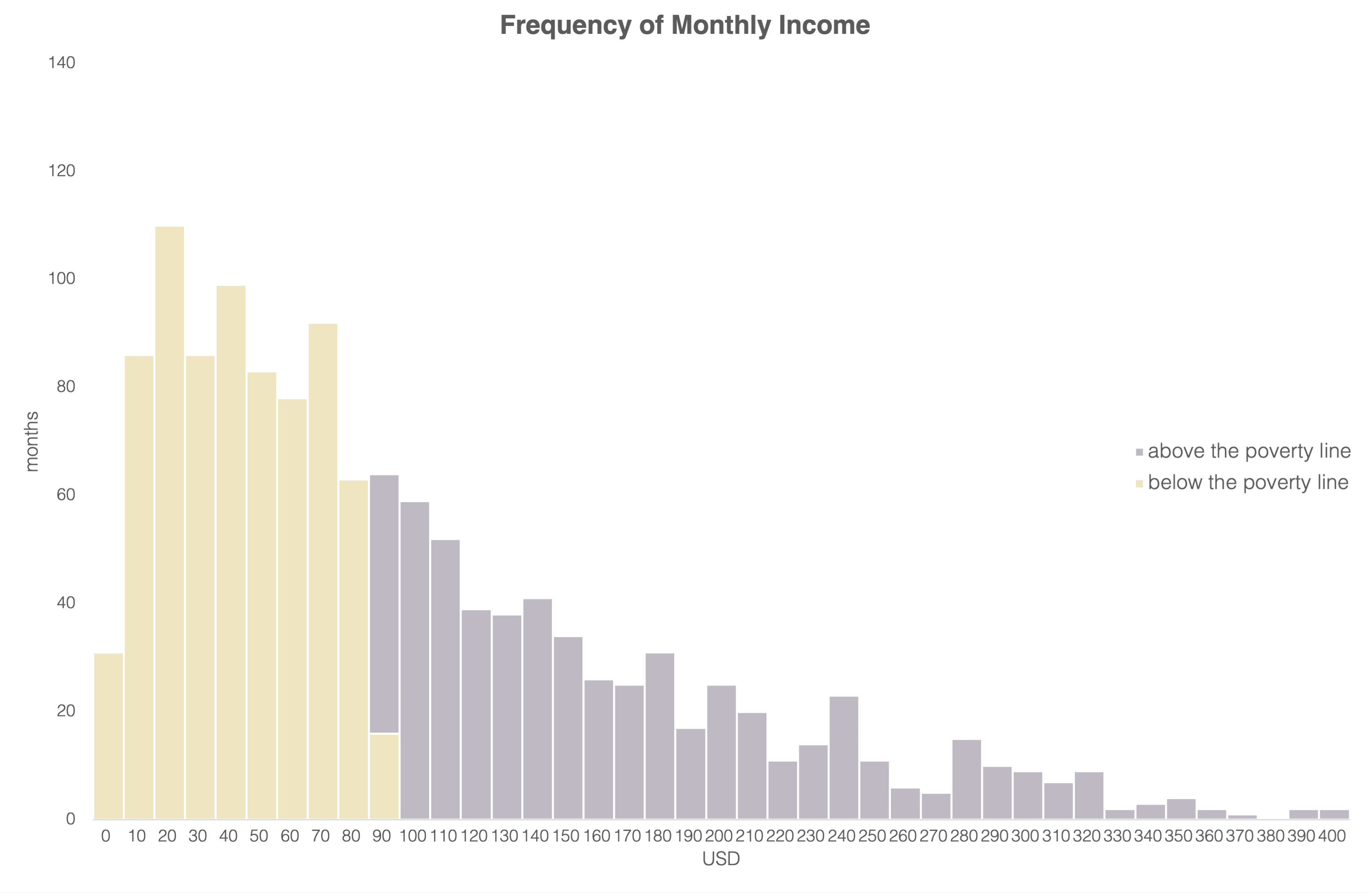

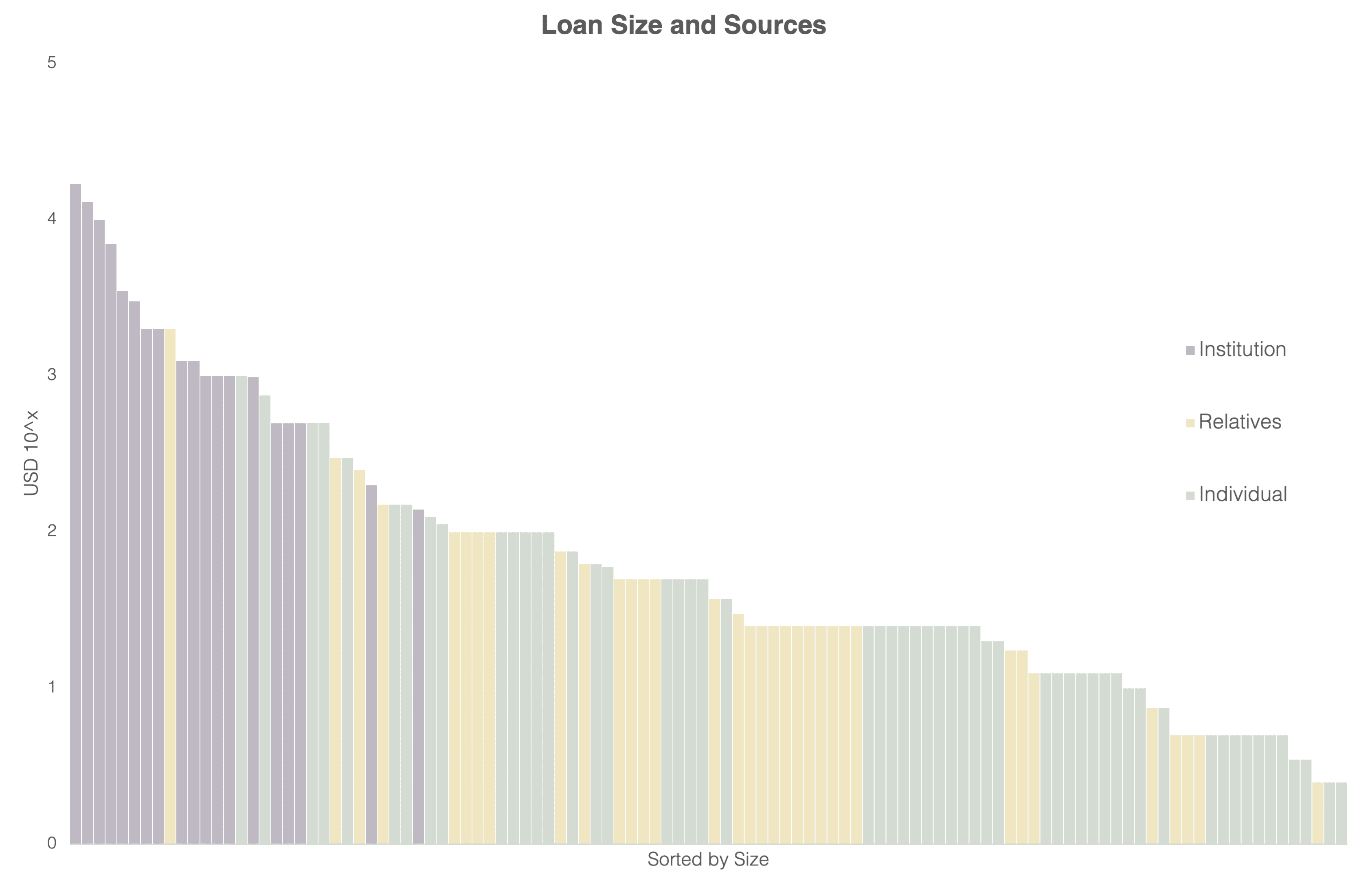

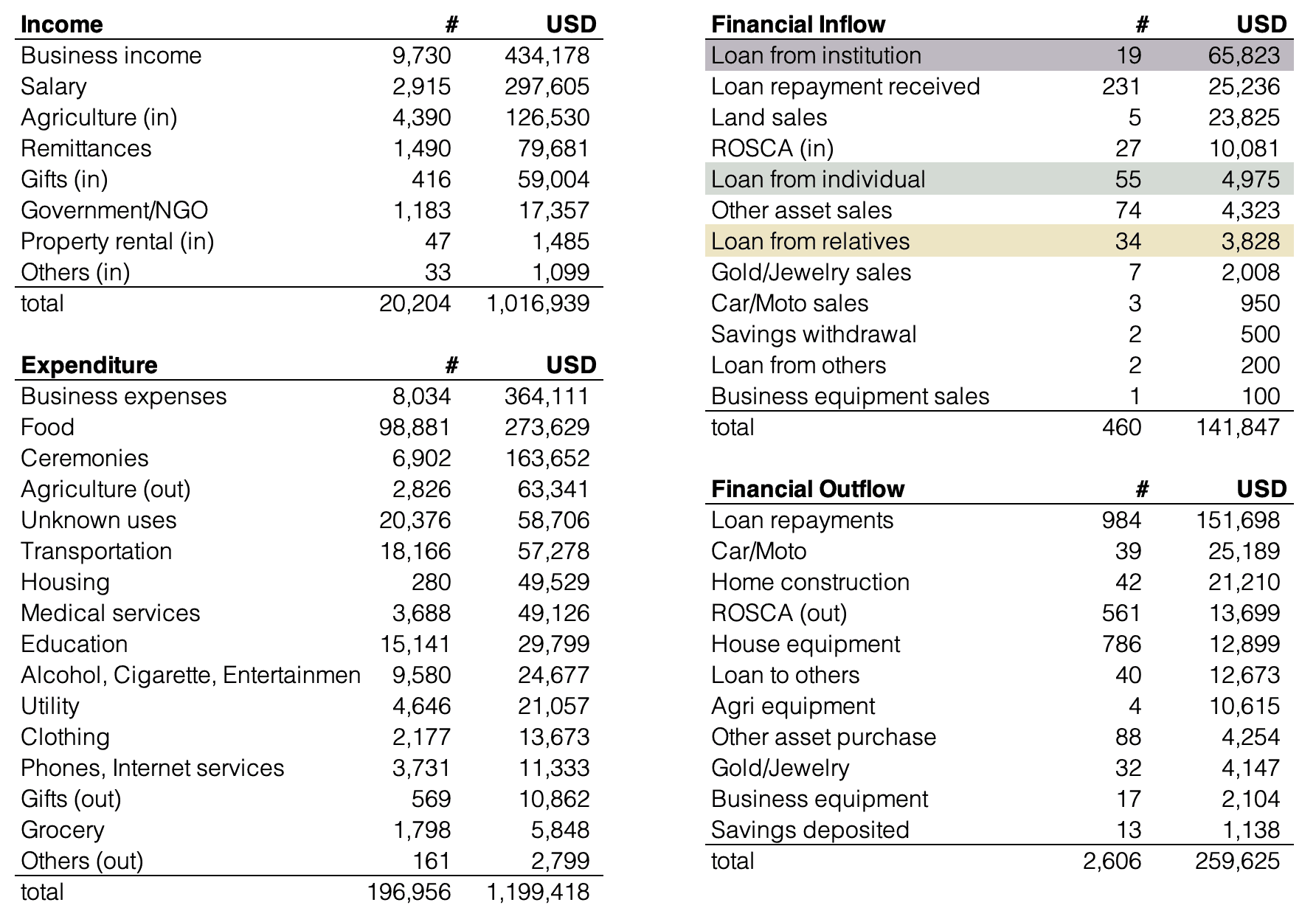

Using data from Stuart Rutherford’s Hrishipara Daily Diaries project, we would like to introduce a new impact measure which looks at how financial services either reduce or add to the volatility of a person’s cash flows. Our working assumption is that services which increase cash flow volatility generally make money harder to manage, and vice versa. We call this measure of impact on volatility the Fit Factor.

Read our paper setting out the concept, its applications as an impact measure, and its limitations here.

Yoshinari Noguchi is a researcher at Gojo and Company. He works in Gojo’s R&D team, and is currently looking into new ways to understand and support money management for low-income people, as well as analysis of data from the Hrishipara diaries and Gojo’s own financial diary projects.

Cheriel Neo leads impact measurement at Gojo and is also a member of Gojo’s R&D team. She is setting up and running Gojo’s financial diary projects in Cambodia and Sri Lanka, and is interested in using data to better understand Gojo’s current and target clients.

In this blog post we introduce The Fit Factor: Matching Loans and Savings to Cash Flows, a new paper from Gojo’s R&D team.

Typically, when we set out to measure the impact of a loan on someone’s life, we tend to look at what happens after they take the loan— for instance, whether their income increases, whether they are able to spend more on education, or whether they acquire more assets. However, there are a couple of limitations to this approach:

- Outcomes data taken following a loan tends to be a snapshot of a certain point in time, and is usually collected at a time pre-determined by the service provider, rather than at a time that makes sense for the borrower in terms of when they expect to see results from the loan

- Changes in income and increased spending on education can be influenced by many different factors in a person’s life, not just their access to finance. For instance, we see in financial diary research that unexpected events happen more often than we might think, such as accidents, sudden medical needs, new opportunities, and other events which may disrupt the original plans a borrower had for their loan

While outcomes data is useful, it cannot give us the full picture of the utility provided by a loan or other financial service. What if, in addition to outcomes data, we considered the impact of a financial service from a cash flow perspective? In other words, what if we could see how loans or savings fit with clients’ real cash flows and affect their day-to-day money management?

Using data from Stuart Rutherford’s Hrishipara Daily Diaries project, we would like to introduce a new impact measure which looks at how financial services either reduce or add to the volatility of a person’s cash flows. Our working assumption is that services which increase cash flow volatility generally make money harder to manage, and vice versa. We call this measure of impact on volatility the Fit Factor.

Read our paper setting out the concept, its applications as an impact measure, and its limitations here.

Yoshinari Noguchi is a researcher at Gojo and Company. He works in Gojo’s R&D team, and is currently looking into new ways to understand and support money management for low-income people, as well as analysis of data from the Hrishipara diaries and Gojo’s own financial diary projects.

Cheriel Neo leads impact measurement at Gojo and is also a member of Gojo’s R&D team. She is setting up and running Gojo’s financial diary projects in Cambodia and Sri Lanka, and is interested in using data to better understand Gojo’s current and target clients.

I'd always thought I'd had a poor childhood. But it wasn’t until I lived and worked in East Africa, India, and Sri Lanka for years that I learnt the true meaning of poverty.

When I first landed in Kenya, I was like any passionate young professional aspiring to create impact for the local poor people. I visited slums and rural areas where I saw muddy roads, kids with dirty clothes, trash everywhere, terrible public toilets. I thought to myself: "This is what poverty looks like".

If my journey of understanding poverty had ended there, it's very likely I'd have come up with solutions such as building a clean public toilet, donating good quality second-hand clothes, or hosting neighbourhood cleaning events to pick up trash, etc - all these things we often see or hear about. These are all nice solutions to temporarily treat pain, but very rarely have they worked for poor people and changed their situation permanently.

Why is that?

Because all these - muddy roads, dirty clothes, terrible toilets - are not what poverty is about.

1. Poverty means: Lack of quality options

The first time I met David (not his real name) was in 2016. He sang in a band at night, but what actually paid his living was picking up garbage in slums and reselling electronic parts. He grew up in a slum with his sister, raised by a single mum. When he was eight and his sister was twelve, they were kicked out by their mum. She told them, "You guys are grown ups now. You need to make a living on your own."

That was the beginning of his criminal teenage years.

The options he had were very limited: 1) Starve and try to find some leftover food in trash bins, or; 2) Transport a small bag of "flour" and get some pennies to fill his stomach. (Nobody suspects a kid with a small bag walking down the street.) As a result, he did both.

I tried to imagine what I’d do, if the same thing happened to me. I would have had many good options- I could have gone to my aunt, to the police,or to a teacher. In fact, I think before doing anything on my own, society would have noticed me and offered to help.

Not one of these options was available to my friend David. And that's what poverty actually means: a lack of quality options. A mother who lives in poverty is not deliberately making a choice to dress her kid in dirty clothes rather than clean second-hand clothes; she is choosing between providing clean clothes and getting food on the table. Most of the time, people do not have real choices.

2. Poverty means: Extremely low value of time

We often hear the phrase "Time is money". When you are poor, you have to spend a lot of time just to get a little bit of money. According to a report, Nairobi ranks as the world's 4th most congested city. This is attributed to the lack of a scheduled public transport system and an underdeveloped non-motorized transport network--again, contributing to a lack of quality choices.

Most people who live in slums work outside the slums. They go to nice neighbourhoods to work as maids, guards, construction labourers, and so on. Travel can take up to 2-3 hours each way. That is 4-6 hours every day, just gone, sitting in a matatu (a share taxi). And for safety’s sake, there is absolutely nothing you can do in a matatu, not even using your smartphone.

Transportation is just one example. The effects of this low value of time pervade every aspect of daily life. Everything takes so much more time for a poor person than for a middle-class person. And the less time you have to earn and learn, the less valuable your time will be. It's a poverty trap.

3. Poverty depends on context

When I learnt that poverty actually means 1) lack of quality choices and 2) extremely low value of time, my perception of so-called "poor neighbourhoods" started to change.

In India, I visited some communities in Himalayan regions which have very basic infrastructure, lacking even mobile phone signal. Their clothes are not clean and shiny; they still use traditional toilets; and their incomes are generally low and unstable. However, their neighbourhoods and environment provide an abundance of quality options for water, food, and entertainment, and they have plenty of time for themselves!

Just by looking at the numbers, they may be classified as households in poverty. But in my view, they simply have a different reality of life from those of us who live in developed countries. In our context, their standard of living would be considered poverty; in their context, it's just a normal neighbourhood. And if we force changes on their neighbourhood simply because we judge that they are in poverty based on some numbers on a page, the damage could be catastrophic.

This might be a reason why so many social innovation ideas have failed or even created greater harm than positive impact. Poverty depends on one’s context. Forcing one's expectations onto someone else’s context can lead to disastrous outcomes.

As Gojo works on extending financial inclusion to everyone, we need to understand what poverty and lack of financial inclusion mean to our clients. We must always try our best to listen first to understand and respect our clients' context and to create a solution which truly works for them.

Yung Han Chang works on Corporate Planning and Investor Relations at Gojo, drawing on her prior experience in Sri Lanka as a country rep for Gojo and in Kenya at the Amani Institute, where she completed a post-graduate certificate in Social Innovation Management. She is currently working on Gojo's long-term strategy and governance processes.

I'd always thought I'd had a poor childhood. But it wasn’t until I lived and worked in East Africa, India, and Sri Lanka for years that I learnt the true meaning of poverty.

When I first landed in Kenya, I was like any passionate young professional aspiring to create impact for the local poor people. I visited slums and rural areas where I saw muddy roads, kids with dirty clothes, trash everywhere, terrible public toilets. I thought to myself: "This is what poverty looks like".

If my journey of understanding poverty had ended there, it's very likely I'd have come up with solutions such as building a clean public toilet, donating good quality second-hand clothes, or hosting neighbourhood cleaning events to pick up trash, etc - all these things we often see or hear about. These are all nice solutions to temporarily treat pain, but very rarely have they worked for poor people and changed their situation permanently.

Why is that?

Because all these - muddy roads, dirty clothes, terrible toilets - are not what poverty is about.

1. Poverty means: Lack of quality options

The first time I met David (not his real name) was in 2016. He sang in a band at night, but what actually paid his living was picking up garbage in slums and reselling electronic parts. He grew up in a slum with his sister, raised by a single mum. When he was eight and his sister was twelve, they were kicked out by their mum. She told them, "You guys are grown ups now. You need to make a living on your own."

That was the beginning of his criminal teenage years.

The options he had were very limited: 1) Starve and try to find some leftover food in trash bins, or; 2) Transport a small bag of "flour" and get some pennies to fill his stomach. (Nobody suspects a kid with a small bag walking down the street.) As a result, he did both.

I tried to imagine what I’d do, if the same thing happened to me. I would have had many good options- I could have gone to my aunt, to the police,or to a teacher. In fact, I think before doing anything on my own, society would have noticed me and offered to help.

Not one of these options was available to my friend David. And that's what poverty actually means: a lack of quality options. A mother who lives in poverty is not deliberately making a choice to dress her kid in dirty clothes rather than clean second-hand clothes; she is choosing between providing clean clothes and getting food on the table. Most of the time, people do not have real choices.

2. Poverty means: Extremely low value of time

We often hear the phrase "Time is money". When you are poor, you have to spend a lot of time just to get a little bit of money. According to a report, Nairobi ranks as the world's 4th most congested city. This is attributed to the lack of a scheduled public transport system and an underdeveloped non-motorized transport network--again, contributing to a lack of quality choices.

Most people who live in slums work outside the slums. They go to nice neighbourhoods to work as maids, guards, construction labourers, and so on. Travel can take up to 2-3 hours each way. That is 4-6 hours every day, just gone, sitting in a matatu (a share taxi). And for safety’s sake, there is absolutely nothing you can do in a matatu, not even using your smartphone.

Transportation is just one example. The effects of this low value of time pervade every aspect of daily life. Everything takes so much more time for a poor person than for a middle-class person. And the less time you have to earn and learn, the less valuable your time will be. It's a poverty trap.

3. Poverty depends on context

When I learnt that poverty actually means 1) lack of quality choices and 2) extremely low value of time, my perception of so-called "poor neighbourhoods" started to change.

In India, I visited some communities in Himalayan regions which have very basic infrastructure, lacking even mobile phone signal. Their clothes are not clean and shiny; they still use traditional toilets; and their incomes are generally low and unstable. However, their neighbourhoods and environment provide an abundance of quality options for water, food, and entertainment, and they have plenty of time for themselves!

Just by looking at the numbers, they may be classified as households in poverty. But in my view, they simply have a different reality of life from those of us who live in developed countries. In our context, their standard of living would be considered poverty; in their context, it's just a normal neighbourhood. And if we force changes on their neighbourhood simply because we judge that they are in poverty based on some numbers on a page, the damage could be catastrophic.

This might be a reason why so many social innovation ideas have failed or even created greater harm than positive impact. Poverty depends on one’s context. Forcing one's expectations onto someone else’s context can lead to disastrous outcomes.

As Gojo works on extending financial inclusion to everyone, we need to understand what poverty and lack of financial inclusion mean to our clients. We must always try our best to listen first to understand and respect our clients' context and to create a solution which truly works for them.

Yung Han Chang works on Corporate Planning and Investor Relations at Gojo, drawing on her prior experience in Sri Lanka as a country rep for Gojo and in Kenya at the Amani Institute, where she completed a post-graduate certificate in Social Innovation Management. She is currently working on Gojo's long-term strategy and governance processes.

Over the past decade, the rise of impact investing has been accompanied by the rise of the term impact measurement. Sir Ronald Cohen, one of the most prominent pioneers of impact investing, has been particularly influential in this area.

For investors, impact measurement makes sense and is important to do. As proponents of impact measurement say, standardised impact measures enable resources to be allocated to the most effective enterprises, and can help to grow the sector by attracting increasing numbers of socially conscious investors.

When it comes to service providers, however, I’ve found that the motivation to measure impact is often externally focused, and I think this has to do with the fact that the push for impact measurement has largely been led by investors. Many frontline service providers see impact measurement’s primary benefit as supporting marketing and fundraising, to the extent that organisations often assign the same team member to both marketing and impact measurement. Impact measurement tends to be seen as, at best, a nice-to-have, and, at worst, an expensive imposition.

Nonetheless, there are really good reasons for service providers to measure their impact— reasons that are more about building better businesses than about demonstrating results to external stakeholders. It’s simply that the prevalent framing of impact measurement isn’t helping people to see this— and impact cannot begin to be meaningfully measured without a genuine commitment from service providers.

If impact measurement is to be valued by service providers, then it needs to be framed in a way that serves their needs. I don’t think the value proposition of impact measurement for service providers ought to be about gathering sufficiently impressive numbers, or even necessarily about measuring long-term, sustained impact1, as such.What can make impact measurement truly valuable for service providers is the way it facilitates learning— learning about the people we work with and the role our services play in their lives, learning about the gaps between our assumptions and reality, and learning about how we can bring our theories of change and our actions ever closer to the reality of clients’ lives.

I’ve found, however, that the use of impact measurement for practical learning can be hampered by the perception that service providers need to be collecting standardised, comparable data on impact (as opposed to outcomes) for the benefit of external stakeholders. This perception can encourage:

- A bias towards measuring positive impact

- A preference for a static set of indicators rather than a dynamic and evolving set

- A view that impact happens so far in the future that young organisations cannot measure it, short feedback loops cannot be built around it, and that impact measurement therefore has no bearing on what an organisation does today or tomorrow

At least initially, prioritising learning in impact measurement could mean sacrificing some of the sacred cows of existing systems and frameworks, such as a focus on standardisation or on long-term, rigorously verifiable impact. It’s not that these things aren’t important— but that impact measurement which is of practical use to service providers is not high-level or long-term, but rather specific, dynamic, and of immediate relevance.

Given enough time to bed in, an organisation might pursue all these things at once. But getting impact measurement off the ground within the limited resources of frontline service providers means prioritising usefulness, and prioritising usefulness could mean sacrificing high-level, comparable data for depth of understanding in a specific area. It might mean giving up a comprehensive, standardised set of measures in favour of a dynamic set of metrics that evolves as we learn. At least at first, it might mean focusing on more directly attributable outcomes rather than wider or longer-term impact.

For an enterprise with social goals, its degree of commitment to impact measurement can be seen as a proxy for the value it places on learning and innovation. While a commitment to learning or lack thereof might not make or break an organisation in the next six, or even twelve, months, it will ultimately be essential to the medium and long-term survival and flourishing of the organisation.

Having encountered the above tensions and trade-offs a fair few times now, I thought it would be worth nailing my colours to the mast and sharing my rules of thumb in designing practical impact measures at Gojo, in the form of a manifesto.

I’d love to hear from colleagues in the sector about whether these ideas resonate with you.

An Impact Measurement manifesto for service providers (inspired by the Agile Manifesto)

We value:

Quality over quantity

Learning over marketing

Long-term relationship over short-term benefit

Building on existing data and processes over introducing something entirely new

Starting with small, immediate outcomes now before gathering comprehensive data on long-term impact later

While we believe in the need to balance the things on the left with the things on the right, we value the things on the left more and will put them first.

Further reading

The Social Performance Task Force’s Outcomes Working Group is doing a great job of creating practical, useful guidelines for service providers. For further reading, I’d recommend their Case for Outcomes Management and Guidelines on Outcomes Management.

Cheriel leads impact measurement at Gojo. She is currently working on implementing impact measures in Gojo's partner companies and planning a financial diaries project.

Over the past decade, the rise of impact investing has been accompanied by the rise of the term impact measurement. Sir Ronald Cohen, one of the most prominent pioneers of impact investing, has been particularly influential in this area.

For investors, impact measurement makes sense and is important to do. As proponents of impact measurement say, standardised impact measures enable resources to be allocated to the most effective enterprises, and can help to grow the sector by attracting increasing numbers of socially conscious investors.

When it comes to service providers, however, I’ve found that the motivation to measure impact is often externally focused, and I think this has to do with the fact that the push for impact measurement has largely been led by investors. Many frontline service providers see impact measurement’s primary benefit as supporting marketing and fundraising, to the extent that organisations often assign the same team member to both marketing and impact measurement. Impact measurement tends to be seen as, at best, a nice-to-have, and, at worst, an expensive imposition.

Nonetheless, there are really good reasons for service providers to measure their impact— reasons that are more about building better businesses than about demonstrating results to external stakeholders. It’s simply that the prevalent framing of impact measurement isn’t helping people to see this— and impact cannot begin to be meaningfully measured without a genuine commitment from service providers.

If impact measurement is to be valued by service providers, then it needs to be framed in a way that serves their needs. I don’t think the value proposition of impact measurement for service providers ought to be about gathering sufficiently impressive numbers, or even necessarily about measuring long-term, sustained impact1, as such.What can make impact measurement truly valuable for service providers is the way it facilitates learning— learning about the people we work with and the role our services play in their lives, learning about the gaps between our assumptions and reality, and learning about how we can bring our theories of change and our actions ever closer to the reality of clients’ lives.

I’ve found, however, that the use of impact measurement for practical learning can be hampered by the perception that service providers need to be collecting standardised, comparable data on impact (as opposed to outcomes) for the benefit of external stakeholders. This perception can encourage:

- A bias towards measuring positive impact

- A preference for a static set of indicators rather than a dynamic and evolving set

- A view that impact happens so far in the future that young organisations cannot measure it, short feedback loops cannot be built around it, and that impact measurement therefore has no bearing on what an organisation does today or tomorrow

At least initially, prioritising learning in impact measurement could mean sacrificing some of the sacred cows of existing systems and frameworks, such as a focus on standardisation or on long-term, rigorously verifiable impact. It’s not that these things aren’t important— but that impact measurement which is of practical use to service providers is not high-level or long-term, but rather specific, dynamic, and of immediate relevance.

Given enough time to bed in, an organisation might pursue all these things at once. But getting impact measurement off the ground within the limited resources of frontline service providers means prioritising usefulness, and prioritising usefulness could mean sacrificing high-level, comparable data for depth of understanding in a specific area. It might mean giving up a comprehensive, standardised set of measures in favour of a dynamic set of metrics that evolves as we learn. At least at first, it might mean focusing on more directly attributable outcomes rather than wider or longer-term impact.

For an enterprise with social goals, its degree of commitment to impact measurement can be seen as a proxy for the value it places on learning and innovation. While a commitment to learning or lack thereof might not make or break an organisation in the next six, or even twelve, months, it will ultimately be essential to the medium and long-term survival and flourishing of the organisation.

Having encountered the above tensions and trade-offs a fair few times now, I thought it would be worth nailing my colours to the mast and sharing my rules of thumb in designing practical impact measures at Gojo, in the form of a manifesto.

I’d love to hear from colleagues in the sector about whether these ideas resonate with you.

An Impact Measurement manifesto for service providers (inspired by the Agile Manifesto)

We value:

Quality over quantity

Learning over marketing

Long-term relationship over short-term benefit

Building on existing data and processes over introducing something entirely new

Starting with small, immediate outcomes now before gathering comprehensive data on long-term impact later

While we believe in the need to balance the things on the left with the things on the right, we value the things on the left more and will put them first.

Further reading

The Social Performance Task Force’s Outcomes Working Group is doing a great job of creating practical, useful guidelines for service providers. For further reading, I’d recommend their Case for Outcomes Management and Guidelines on Outcomes Management.

Cheriel leads impact measurement at Gojo. She is currently working on implementing impact measures in Gojo's partner companies and planning a financial diaries project.

Sign up to receive news from Gojo here.