If we look back at the history of accounting, it has been changing and improving constantly since its birth, and the scope it is covering is spreading and adapting with the ever-changing world of business.

If we look back at the history of accounting, it has been changing and improving constantly since its birth, and the scope it is covering is spreading and adapting with the ever-changing world of business.

In order to speed up loan approval processes, many banks and microfinance institutions use computer algorithms to calculate credit scores. I'm sure many of you are familiar with seeing a numerical credit score like '700'.

Credit scoring collects various pieces of information about a loan applicant and maps them to a single number. Based on the applicant’s loan repayment history, their use of other financial services, and other factors, the algorithm calculates a score such as '670 for this applicant', '740 for that applicant', and so on. And if the score is lower than the predefined threshold, the loan will not be approved.

Here, I would like to introduce a little theorem that makes up a part of Gojo's credit scoring approach.

Whether or not you can repay a loan without issues depends to a large extent on the size of the loan. For example, if I take a loan of $1 million, and spend it all at once without thinking, I will probably have a problem repaying it later. However, if I take a loan of $1, and use it to pay for some expenses, I will probably not have a problem repaying it later. In other words, credit scoring, which measures my ability to repay the loan, should be a function of the loan size.

Now, let's extend this view just a little bit more. The larger the loan size, the higher the credit score that should be required for the borrower, and therefore the higher the hurdle. The smaller the loan size, the lower the credit score that should be required for the borrower, and the lower the hurdle.

If that is the case, then for any given borrower, there should be a loan size that represents a manageable hurdle. For any kind of borrower, if we keep reducing the loan size, we will eventually find an amount that matches the maximum credit score they can achieve.

The above paragraphs outline a little theorem about credit scoring, which is my favorite. Of course, we can take a further step to consider how we might apply it in practice.

Why don't we just look for the (maximum) loan size we believe a borrower can handle, and use that as their credit score? Rather than producing a score like '670' or '740', it would be easier for everyone to understand that $500 is the maximum possible amount they would be allowed to borrow. If the amount is clear, borrowers can plan their investment.

We are actually applying this approach in a loan product currently being offered by Maxima, our partner in Cambodia. Their small digital loans project (also known as MBela) uses an automated assessment process to provide a credit score in the form of the maximum amount each person can borrow. The resulting credit score is easy for both the agent and borrower to understand.

Gojo wants to provide services that are innovative in their simplicity.

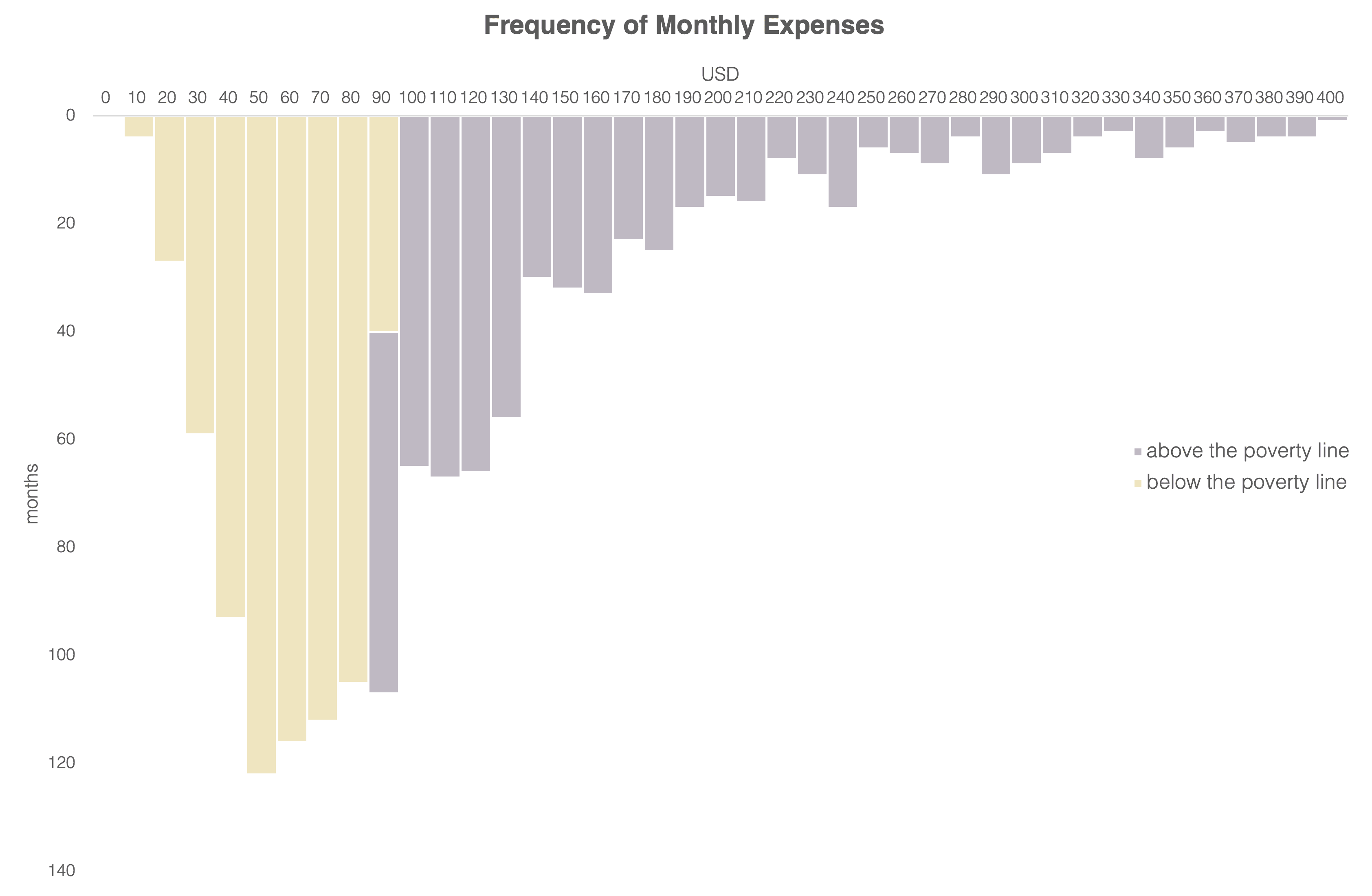

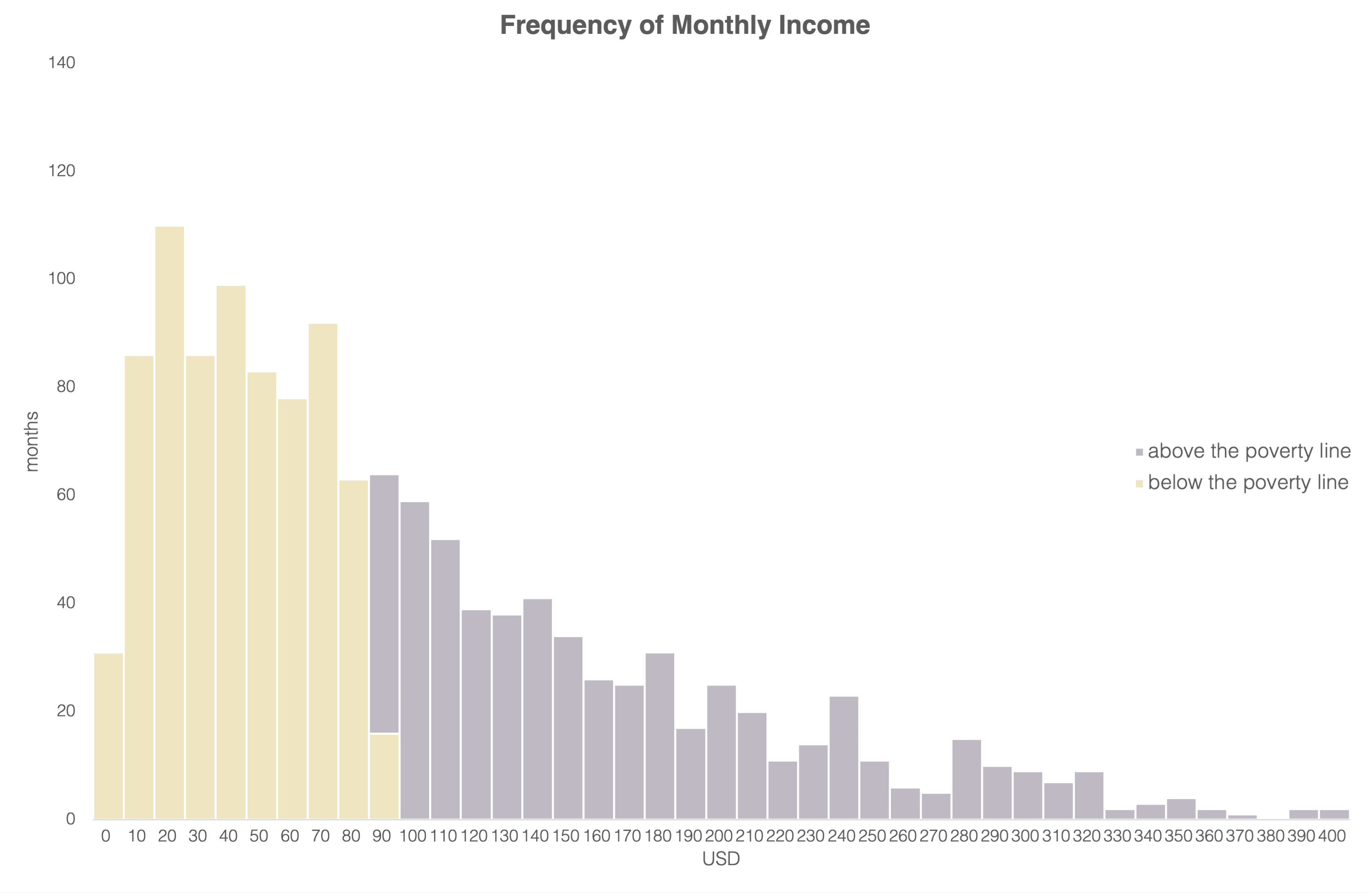

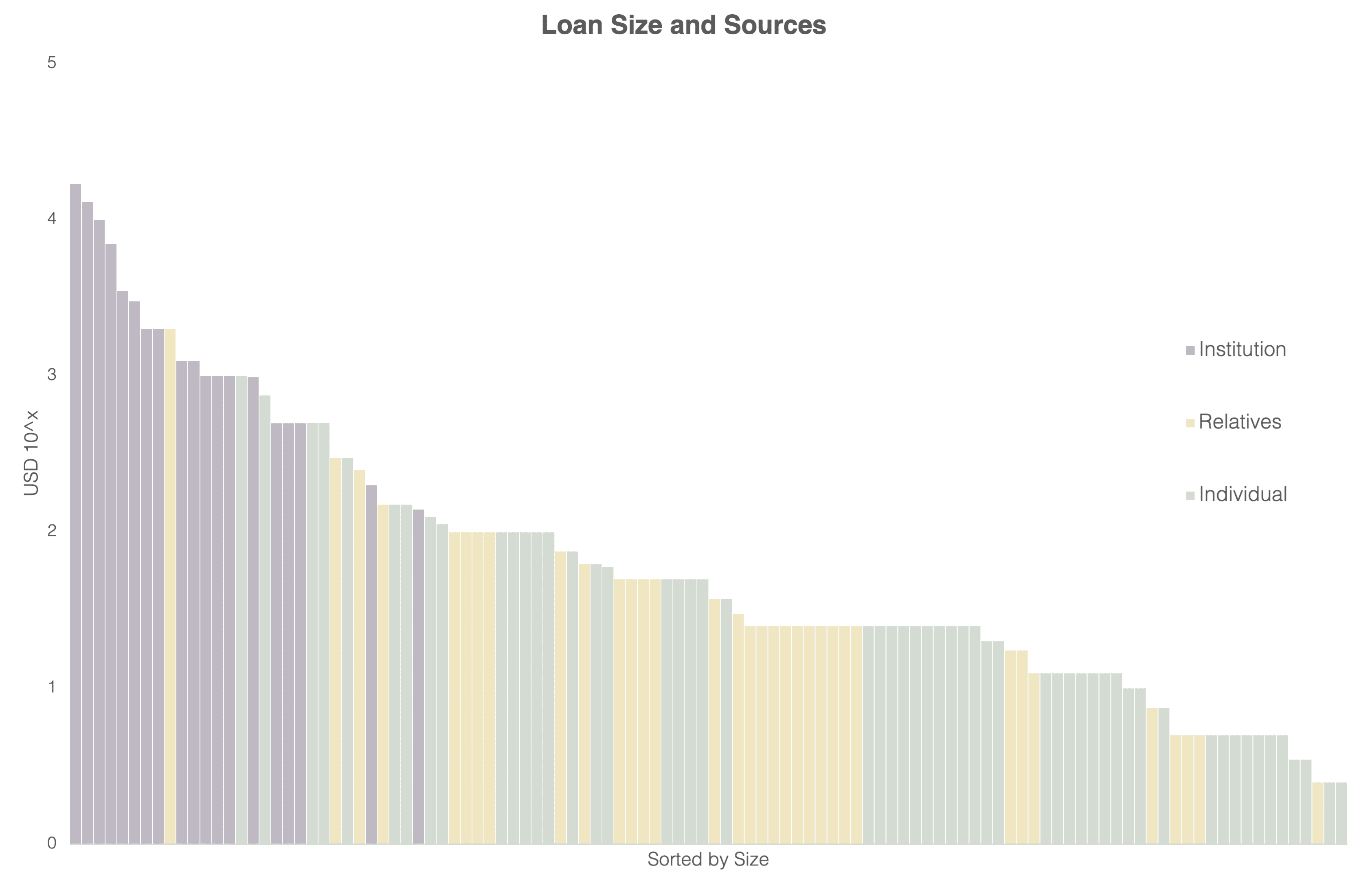

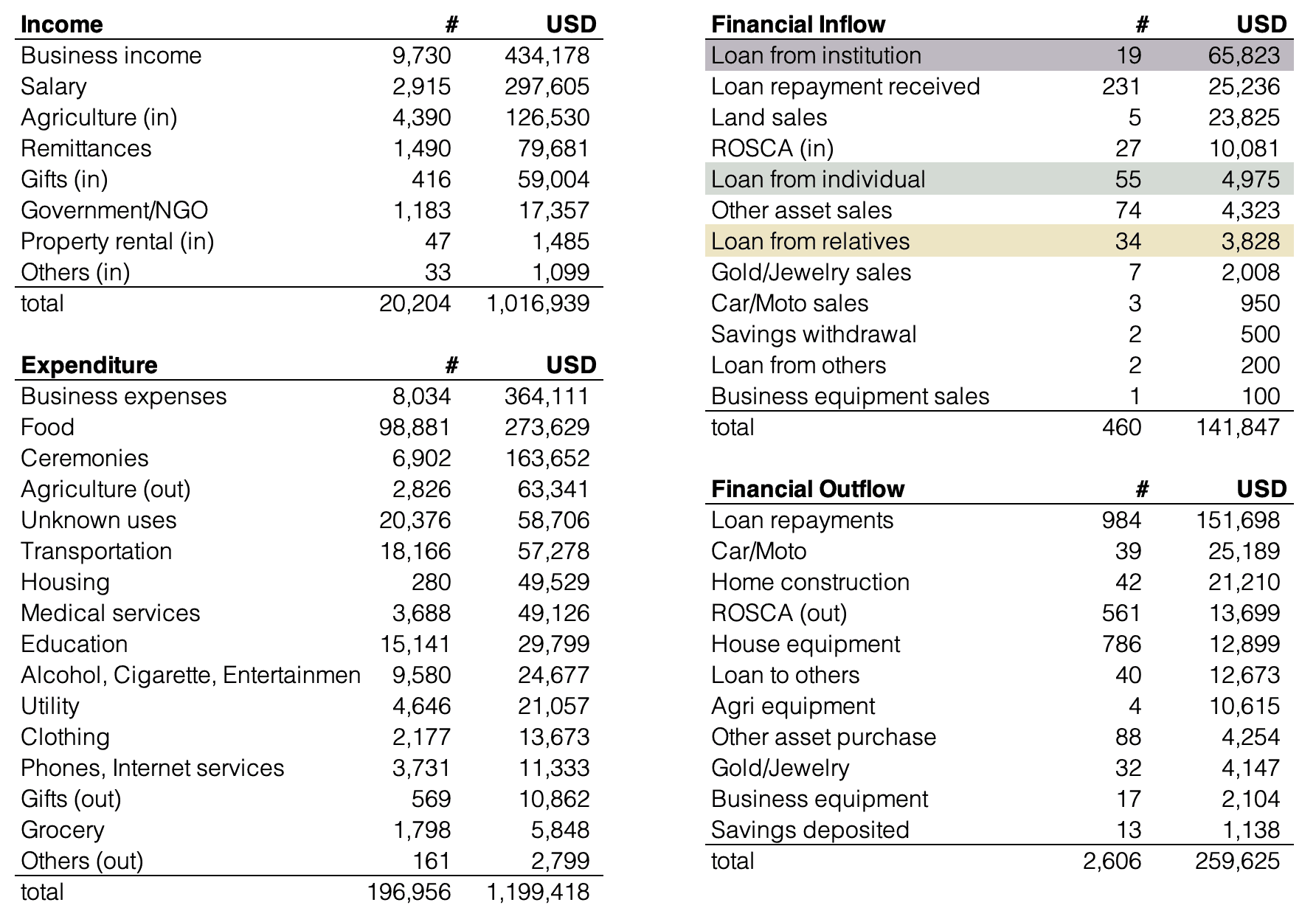

Yoshinari Noguchi is a researcher at Gojo and Company. He works in Gojo’s R&D team, and is currently looking into new ways to understand and support money management for low-income people, as well as analysis of data from the Hrishipara diaries and Gojo’s own financial diary projects.

In order to speed up loan approval processes, many banks and microfinance institutions use computer algorithms to calculate credit scores. I'm sure many of you are familiar with seeing a numerical credit score like '700'.

Credit scoring collects various pieces of information about a loan applicant and maps them to a single number. Based on the applicant’s loan repayment history, their use of other financial services, and other factors, the algorithm calculates a score such as '670 for this applicant', '740 for that applicant', and so on. And if the score is lower than the predefined threshold, the loan will not be approved.

Here, I would like to introduce a little theorem that makes up a part of Gojo's credit scoring approach.

Whether or not you can repay a loan without issues depends to a large extent on the size of the loan. For example, if I take a loan of $1 million, and spend it all at once without thinking, I will probably have a problem repaying it later. However, if I take a loan of $1, and use it to pay for some expenses, I will probably not have a problem repaying it later. In other words, credit scoring, which measures my ability to repay the loan, should be a function of the loan size.

Now, let's extend this view just a little bit more. The larger the loan size, the higher the credit score that should be required for the borrower, and therefore the higher the hurdle. The smaller the loan size, the lower the credit score that should be required for the borrower, and the lower the hurdle.

If that is the case, then for any given borrower, there should be a loan size that represents a manageable hurdle. For any kind of borrower, if we keep reducing the loan size, we will eventually find an amount that matches the maximum credit score they can achieve.

The above paragraphs outline a little theorem about credit scoring, which is my favorite. Of course, we can take a further step to consider how we might apply it in practice.

Why don't we just look for the (maximum) loan size we believe a borrower can handle, and use that as their credit score? Rather than producing a score like '670' or '740', it would be easier for everyone to understand that $500 is the maximum possible amount they would be allowed to borrow. If the amount is clear, borrowers can plan their investment.

We are actually applying this approach in a loan product currently being offered by Maxima, our partner in Cambodia. Their small digital loans project (also known as MBela) uses an automated assessment process to provide a credit score in the form of the maximum amount each person can borrow. The resulting credit score is easy for both the agent and borrower to understand.

Gojo wants to provide services that are innovative in their simplicity.

Yoshinari Noguchi is a researcher at Gojo and Company. He works in Gojo’s R&D team, and is currently looking into new ways to understand and support money management for low-income people, as well as analysis of data from the Hrishipara diaries and Gojo’s own financial diary projects.

I recently completed the financial modelling process for Gojo, and thought that the process might be of interest to other investors in financial inclusion, or anyone interested in the economics of microfinance.

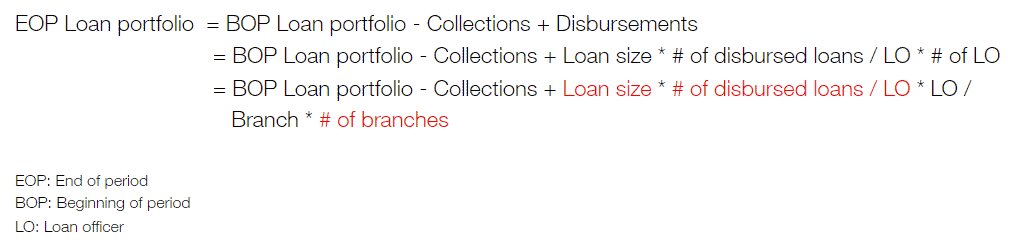

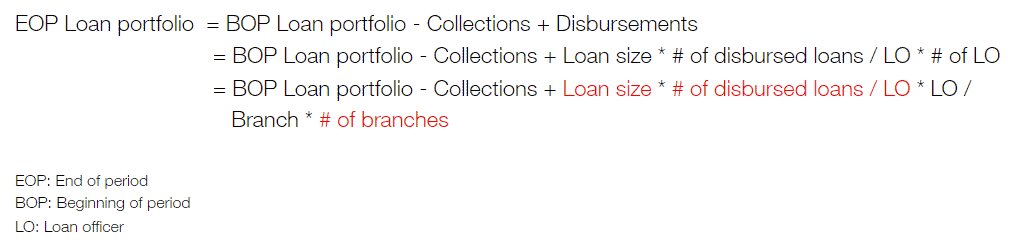

The financial modelling of MFIs is not complicated. Financial Revenue is the key item amongst the other P&L items to understand the structure and assess the scalability of microfinance businesses. It is calculated as interest rate multiplied by Loan Portfolio. In this blog, I would like to focus on the Loan Portfolio because the other factor, the interest rate, is capped by regulators in some countries, and is not always a parameter which MFIs can freely change.

The loan portfolio can be broken down as follows. The 3 items colored in red are the key indicators on which I would like to elaborate further.

- Productivity (# of disbursed loans / LO): One of the most important factors is Productivity, which here means the number of loans disbursed per loan officer. This indicator shows how many loans a loan officer can handle at a time, or how many new loans a loan officer can disburse in a certain period.

This indicator can be further broken down by branch or product. The productivity is highly correlated with branch vintage, i.e. the productivity tends to be lower at a newly opened branch but it improves as time goes by as officers get trained and become more experienced. Also, this indicator can be further improved through streamlining operations / processes through technology, such as the use of a Digital Field Application, automated underwriting, cashless payments etc.

One example of this at Gojo is a Digital Field Application called Bridge, developed by our tech team, whose MVP succeeded in significantly reducing the registration and loan approval time from 3 days to just 40 minutes! With the device, the loan officers are able to spend more time on client sourcing instead of becoming engaged in unproductive paperwork.

- Loan size: MFIs are willing to offer larger loans to customers who have repaid previous loans, as they can see more of the customer’s credit history than before. But for the MFI to be selected as the customer’s lender of choice, they need to keep a good relationship with customers through close and constant communication, otherwise the customers would end up changing their lenders. The MFI offers larger loans when the MFI is confident enough that the customers will repay the loans.

Therefore, to offer larger loans, it is critical for the MFI to have a deep and up-to-date understanding of customers, including but not limited to, their business, financial situation and personal events. Considering this, although I mentioned the role of technology above, the microfinance industry will not immediately transition to fully tech-equipped services, unlike many other industries, but "tech & touch" will be the key concept for MFIs at least for several years going forward. Given that many MFI customers still do not own smartphones/smart wallets, data about their business situation, financial needs and other life events cannot be collected through these kinds of devices but needs to continue being collected through human touch to some extent. Modelling loan size therefore means we have to take into account the MFI's current and future capacity to collect data on customers and assess their creditworthiness.

- Branch expansion (# of branches): Room for branch expansion largely varies by country. For instance, in some countries such as Bangladesh, financial services have already spread widely to the bottom of the pyramid, but other countries still contain large numbers of underbanked or unbanked people. In more competitive markets, the MFI needs to have some unique selling point or advantages compared to existing players, whereas in less competitive markets they would be able to enter more easily.

The decision on whether to open a branch depends on potential demand for credit, risks, economics, the competitive environment, and many other factors. An additional factor to take into account is the strategy of a MFI, as some MFIs focus more on urban areas while others target rural areas. There are financial institutions which do not have physical branches, rather operating through agent networks. For such institutions, we would possibly use the number of agents instead of the number of branches.

Although obviously there are many more factors to be considered when developing a financial model, such as operating expenses, fundraising and so on, I believe these three items above are the most critical and impactful items to microfinance businesses. At Gojo, we have seven partners as of now and while each partner has a different business model, the key financial success factors for most of them are the three I have outlined above.

Ryo Satake is an accountant and works in Gojo's finance and strategy and analytics teams. He recently led the process of financial modelling for Gojo's overall business and has helped to formalise the budgeting and financial reporting processes for Gojo's partner companies.

I recently completed the financial modelling process for Gojo, and thought that the process might be of interest to other investors in financial inclusion, or anyone interested in the economics of microfinance.

The financial modelling of MFIs is not complicated. Financial Revenue is the key item amongst the other P&L items to understand the structure and assess the scalability of microfinance businesses. It is calculated as interest rate multiplied by Loan Portfolio. In this blog, I would like to focus on the Loan Portfolio because the other factor, the interest rate, is capped by regulators in some countries, and is not always a parameter which MFIs can freely change.

The loan portfolio can be broken down as follows. The 3 items colored in red are the key indicators on which I would like to elaborate further.

- Productivity (# of disbursed loans / LO): One of the most important factors is Productivity, which here means the number of loans disbursed per loan officer. This indicator shows how many loans a loan officer can handle at a time, or how many new loans a loan officer can disburse in a certain period.

This indicator can be further broken down by branch or product. The productivity is highly correlated with branch vintage, i.e. the productivity tends to be lower at a newly opened branch but it improves as time goes by as officers get trained and become more experienced. Also, this indicator can be further improved through streamlining operations / processes through technology, such as the use of a Digital Field Application, automated underwriting, cashless payments etc.

One example of this at Gojo is a Digital Field Application called Bridge, developed by our tech team, whose MVP succeeded in significantly reducing the registration and loan approval time from 3 days to just 40 minutes! With the device, the loan officers are able to spend more time on client sourcing instead of becoming engaged in unproductive paperwork.

- Loan size: MFIs are willing to offer larger loans to customers who have repaid previous loans, as they can see more of the customer’s credit history than before. But for the MFI to be selected as the customer’s lender of choice, they need to keep a good relationship with customers through close and constant communication, otherwise the customers would end up changing their lenders. The MFI offers larger loans when the MFI is confident enough that the customers will repay the loans.

Therefore, to offer larger loans, it is critical for the MFI to have a deep and up-to-date understanding of customers, including but not limited to, their business, financial situation and personal events. Considering this, although I mentioned the role of technology above, the microfinance industry will not immediately transition to fully tech-equipped services, unlike many other industries, but "tech & touch" will be the key concept for MFIs at least for several years going forward. Given that many MFI customers still do not own smartphones/smart wallets, data about their business situation, financial needs and other life events cannot be collected through these kinds of devices but needs to continue being collected through human touch to some extent. Modelling loan size therefore means we have to take into account the MFI's current and future capacity to collect data on customers and assess their creditworthiness.

- Branch expansion (# of branches): Room for branch expansion largely varies by country. For instance, in some countries such as Bangladesh, financial services have already spread widely to the bottom of the pyramid, but other countries still contain large numbers of underbanked or unbanked people. In more competitive markets, the MFI needs to have some unique selling point or advantages compared to existing players, whereas in less competitive markets they would be able to enter more easily.

The decision on whether to open a branch depends on potential demand for credit, risks, economics, the competitive environment, and many other factors. An additional factor to take into account is the strategy of a MFI, as some MFIs focus more on urban areas while others target rural areas. There are financial institutions which do not have physical branches, rather operating through agent networks. For such institutions, we would possibly use the number of agents instead of the number of branches.

Although obviously there are many more factors to be considered when developing a financial model, such as operating expenses, fundraising and so on, I believe these three items above are the most critical and impactful items to microfinance businesses. At Gojo, we have seven partners as of now and while each partner has a different business model, the key financial success factors for most of them are the three I have outlined above.

Ryo Satake is an accountant and works in Gojo's finance and strategy and analytics teams. He recently led the process of financial modelling for Gojo's overall business and has helped to formalise the budgeting and financial reporting processes for Gojo's partner companies.

Sign up to receive news from Gojo here.