Myanmar’s financial services industry is nascent compared to the rest of the world, since the country only started to open up after the transition in 2011 from military rule to a civilian government. With the transition came liberalization of the financial services industry, with the Central Bank of Myanmar becoming an autonomous entity, and the enactment of the Microfinance business law in 2012. Since then, the industry has been playing catch up with the rest of the world, specifically in the area of mass market consumer lending.

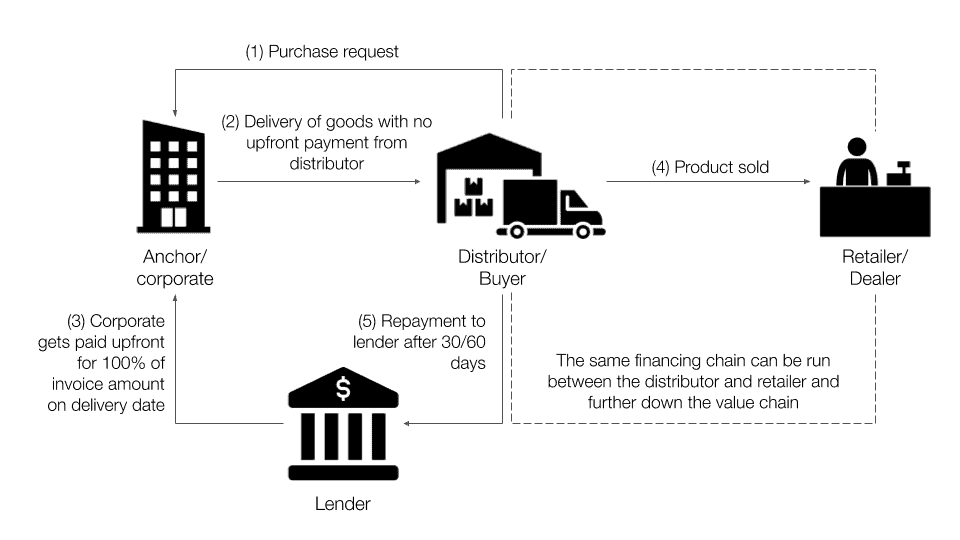

Banks in Myanmar have traditionally served the corporate sector with credit, and have only recently started to slowly expand their reach into the SME sector, with a couple of non-traditional banks dipping their toes into consumer lending. The biggest obstacle banks face is the majority of the population’s lack of credit history. This creates a catch-22 for the risk-averse banking sector, who will not lend to consumers without credit history, but cannot build credit histories for consumers without taking the risk of lending in the first place. Microfinance institutions have been left to pick up where banks fell short in providing lending services to consumers, taking high risk, and building credit histories.

Microfinance in Myanmar started with the mission of getting people out of poverty and extending financial inclusion. The gap in the provision of mainstream financial services has led to the popularity of microfinance among the un/underserved credit-hungry populace. As a result, while maintaining its social mission, the microfinance sector has also grown to be a provider of mass market retail lending, ranging from consumer lending to micro/small business lending. Such rapid expansion in the lending scene has brought the need for credit scoring to the forefront, especially among the no/thin file segment of the population. This is where the sector’s years of trial and error in building the credit history of no/thin file clients can begin to bear fruit, as the sector starts to address the need for stronger credit scoring and risk management by building credit scorecards.

Credit scorecards: An introduction

So, what is a credit scorecard?

It is the heart of credit scoring. It is a checklist of data points that are collected and weighted to spit out a score that we call a credit score, and financial institutions use this score to measure the risk level of a consumer. Consumers who have high credit scores are usually considered low-risk, while consumers on the other end of the spectrum, who have low credit scores, are considered high-risk.

The credit score and its associated risk level can decide whether a consumer gets approved for a loan, the pricing on the loan (risk-weighted pricing), and in some cases, even the loan amount and term. With credit scoring playing an important role in the decision-making process, the need to understand how the credit scorecard is made becomes critical.

A credit scorecard is created by looking at data on past loans that the institution has made so that it can extrapolate its experience of past loans to future consumers. To do this, they first need to classify consumers as either “good” or “bad”, and an analysis is carried out to explore and extract a set of characteristics that makes a borrower “good” or “bad”. In this scenario, the definition of a “bad” consumer, in hindsight, is any consumer to whom the institution would choose not to offer a loan again. There are two main types of scorecards for making such an analysis: an expert scorecard and a statistical scorecard.

Let us begin with the expert scorecard. It is the most basic credit scorecard and the most commonly used scorecard. As its name suggests, it is a scorecard made with inputs from an expert. People with years of experience in lending and credit appraisal make a list of characteristics to check and score for any consumers applying for the loan. This is a very manual process that relies on the personal experience of seasoned loan officers and credit managers in the case of microfinance, and of the underwriting team, in the case of banks.

The statistical scorecard does not draw on any personal experience but instead on statistics. The scorecard is built by using regression analysis to find correlations between data points collected from consumers and the performance of their past loans. This often means that an institution has collected hundreds, if not thousands, of data points from consumers and their past loans to find the correlations.

There is a midway approach, aptly called a hybrid scorecard. This is the combination of the two scorecards where the statistical scorecard is evaluated by experts to create a final version of the scorecard.

Creating a credit scorecard

Financial institutions that are looking to build a scorecard need to evaluate whether they have sufficient data points covering:

- Transaction history (volume and amounts of deposits, withdrawals, cash ins, cash outs, and payments)

- Saving history (balances in individual account or across all deposit accounts)

- Demographics (age, gender, location, etc.)

- Loan performance (number of times a consumer is late for previous loan instalments, number of days late for previous instalments, history of delinquency)

- Income data (individual / consolidated debt to income ratio)

- Relationship with the institution (how long the consumer has been with the institution, other products of the institution used by the consumer)

- Alternative sources of data such as the credit bureau, call/text data, social media usage, etc.

The more data points, the better the statistical scorecard is. If the institution does not have access to or has not accumulated sufficient relevant data points, they can create an initial scorecard by using expert team members who have the experience to make judgement calls in lending, while gradually transitioning towards a statistical scorecard.

Transitioning to a statistical scorecard: The example of MIFIDA

The following is an example of one of Gojo’s partner companies, Microfinance Delta International (MIFIDA), and its journey to create a scorecard.

MIFIDA is a microfinance institution in Myanmar with around 150,000 customers and a portfolio of around $40 million. It was incorporated in 2013 but hit its stride in 2017, when it grew from a handful of branches to 60+ branches today. With such growth, the need to reevaluate its risk management policies and credit assessment became apparent. This in turn highlighted the need for a scorecard for its customers.

MIFIDA already had a scorecard for its MSME customers, but it was a basic expert scorecard that covered the usual characteristics such as: debt coverage ratio, the ratio of repayment amount to income, number of outstanding loans, age, years in the business receiving the loan, etc. But it did not have a scorecard for its mass market lending products, such as its group loans.

MIFIDA therefore set out to reevaluate its current MSME scorecard and to create a new scorecard from scratch for its group loans. Below, I will cover the re-evaluation and update of the MSME scorecard, and the challenges we encountered in the process. I hope to cover our journey toward creating a new scorecard for the group loans in a later post.

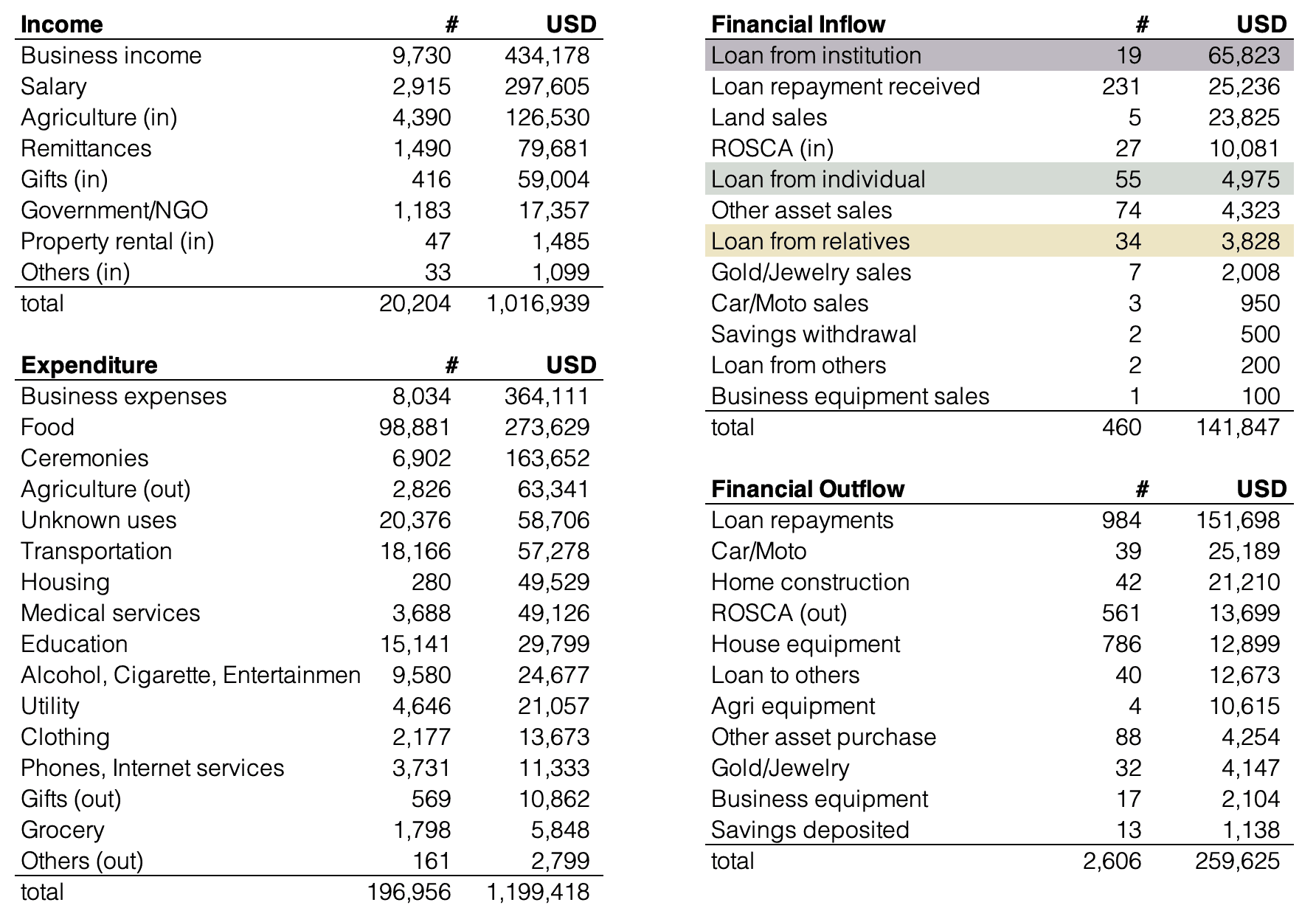

Relevant data is paramount for making a statistical scorecard, and this is exactly what MIFIDA did not have. It had only implemented its core banking system in recent months and even then, it only had transactional data going back as far as the data that had been migrated into the system. Despite being around seven years old, MIFIDA did not have digitised historical data on clients. There was also no guarantee that the digitised data was reliable.

This ruled out immediate creation of the statistical scorecard for MIFIDA, but as they had experts who have been making loan decisions for years now, they decided to create an expert scorecard based on the experience of their staff. They listed down everything that made a consumer “good” and “bad”. From that listing, the team trimmed it down to 14 specific characteristics that would be most telling of the customer’s behavior and provided the weightings on each characteristic to be scored. A new application form was then drafted so that the data needed for scoring could be captured.

Market-wide challenges in credit scoring

MIFIDA is using this new expert scorecard and application form as stepping stones toward a future statistical scorecard of its own. Apart from the lack of data points mentioned above, the current challenges that MIFIDA is facing in creating the statistical scorecard are:

- A lack of data analysts and data scientists in Myanmar. Even if you have the data, there are few people in Myanmar with the skills to do the necessary analytics to build and produce the scorecard. It would require a person well versed in R or Python to handle large datasets, do exploratory data analysis, find correlations using regression or one of a few other methods, and then make a production-level scorecard that could be used in the field.

- The lack of a credit bureau. Anyone who wants to double check a customer’s self-reported credit history will simply have to trust the consumer as there is no centralized database to check against. In recent years, MCIX (Myanmar Credit Info Exchange) has started to provide such a service to the microfinance sector, but it is still a nascent endeavour, as it currently only shows some of the loans that the customer has taken from other microfinance institutions, and sharing of delinquency data is still a work in progress. Until MCIX or the national credit bureau are fully-fledged, with the majority of financial institutions onboard, MIFIDA will have to check credit histories either by building these histories itself, or through traditional means such as asking family, relatives or local authorities.

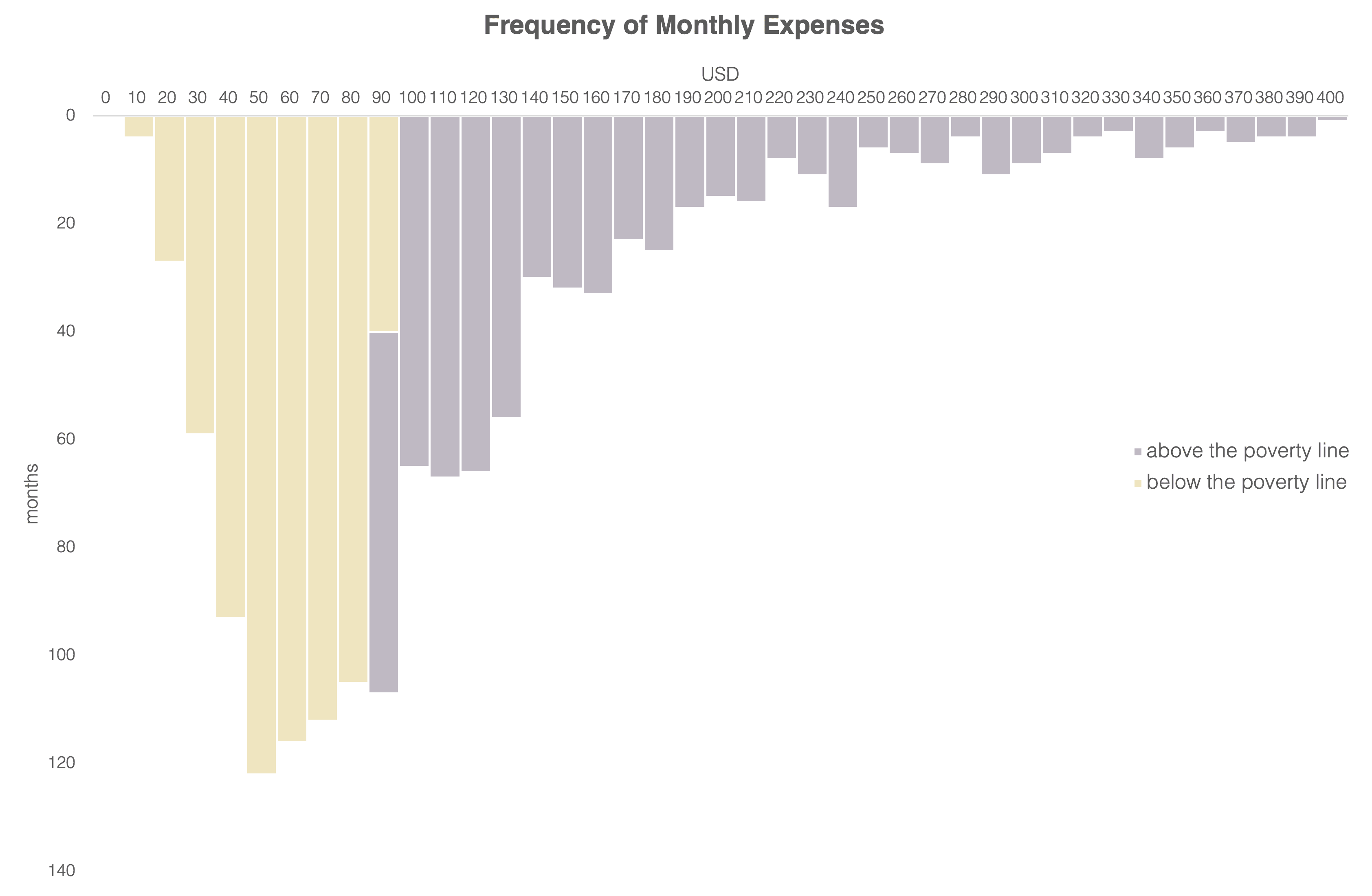

- Tying into the institutional lack of data is that most customers are no/thin file customers who are only just beginning to be financially included. This means that they are at the start of their journey to build a credit history with a formal financial institution. Building such histories takes time. On the other hand, it also presents an opportunity to financial service providers to get the data they want to collect from customers right, so that it can be processed and used for scoring in the future.

Financial institutions in Myanmar, MIFIDA included, are currently working on overcoming those challenges of building a statistical scorecard and transitioning from expert scorecards, as there is a whole world of new opportunities if the transition is successful.

The rewards of better credit scoring

Myanmar has seen one example of an institution that is inching closer to a full statistical scorecard, and the opportunity this has provided to that institution.

The institution is Yoma Bank. Their digital lending product, called SMART Credit, is made for the mass market with a hybrid scorecard in the backend that is recalibrated every year with the help of Experian, one of the biggest providers of credit scoring and analytics in the world. This has helped Yoma Bank to expand its lending portfolio to everyday consumers and to a new market segment that it would not normally lend to due to the associated risk.

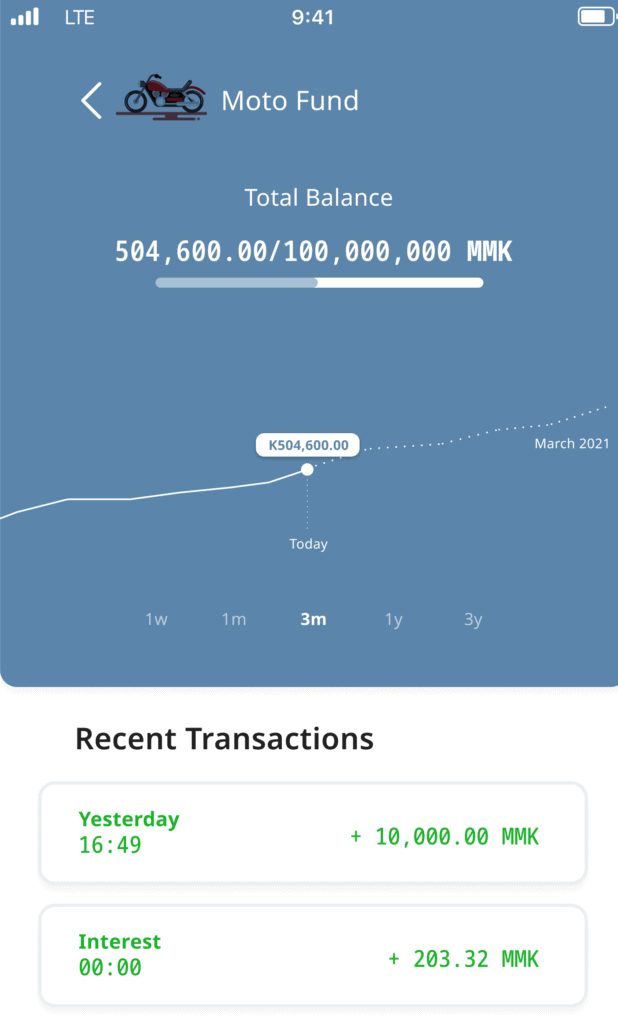

MIFIDA hopes to replicate that success by building its own customers’ credit history, while using an expert scorecard to mitigate the current risks until sufficient data is collected for a statistical scorecard. MIFIDA will also look to move onto digital lending and digitizing much of its operations so that its loan officers can focus more on building relationships with customers instead of focusing on application forms and transactions. Such digitization would allow for the collection of well-structured data points that could be used to move onto a statistical model, enabling MIFIDA to expand more easily to new customer segments with reduced risk in future by providing a comparable baseline for the new segment’s credit scoring.

Kaung Set Lin is Gojo's Country Officer for Myanmar, and has over 6 years of experience in Myanmar's financial sector, primarily focusing on developing and implementing digital financial products. His work includes managing the rollout of Gojo's digital products, including our Digital Field Application (DFA).