Our CEO Taejun was recently interviewed by Dr Vic Woo of Stanford University on the new sustainability-focused RESET podcast. In this episode, he shares the story of how he founded Gojo and the thinking behind our investment strategy.

I recently completed the financial modelling process for Gojo, and thought that the process might be of interest to other investors in financial inclusion, or anyone interested in the economics of microfinance.

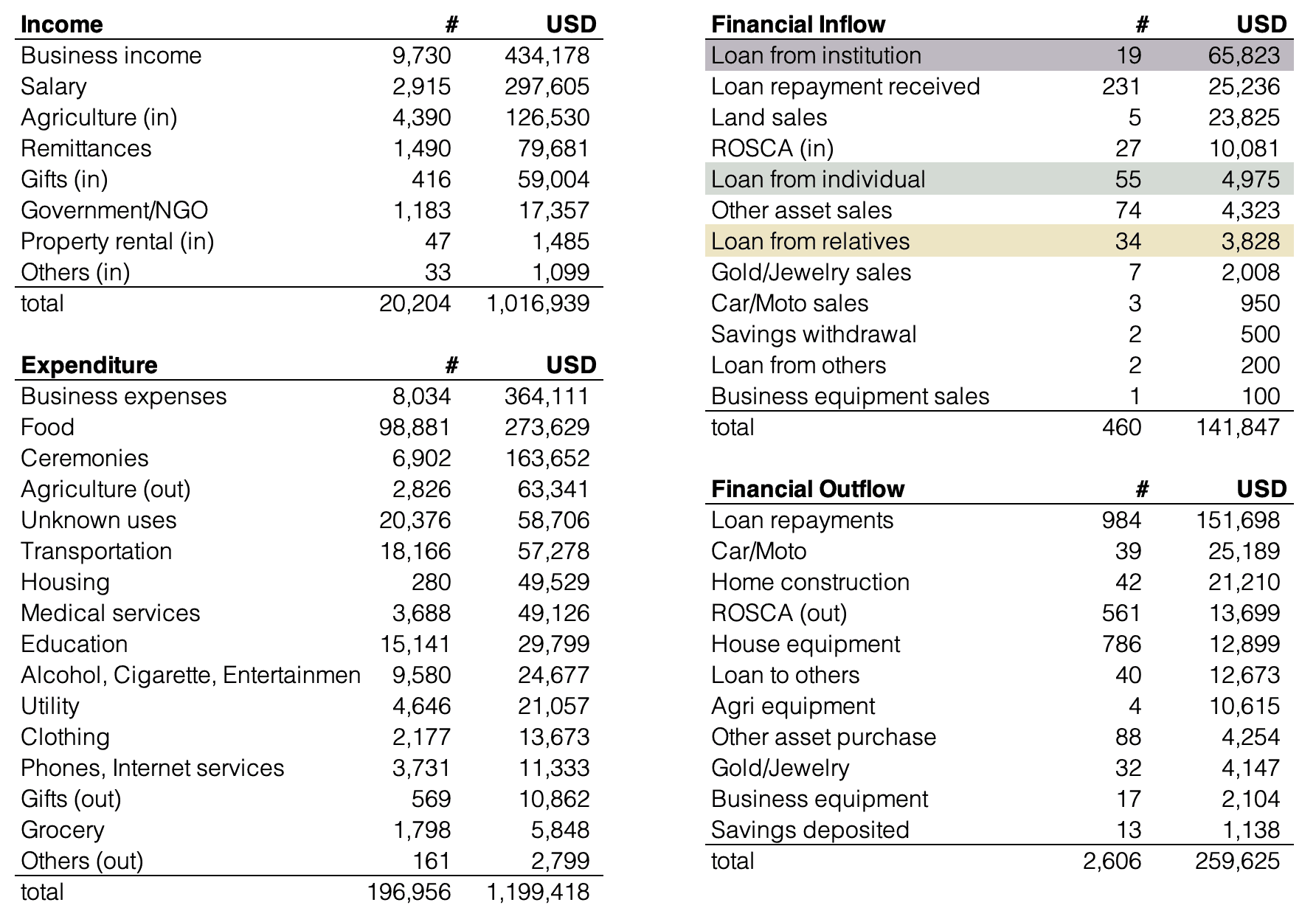

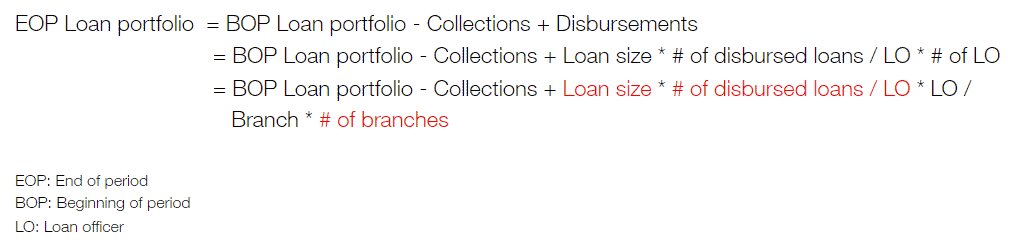

The financial modelling of MFIs is not complicated. Financial Revenue is the key item amongst the other P&L items to understand the structure and assess the scalability of microfinance businesses. It is calculated as interest rate multiplied by Loan Portfolio. In this blog, I would like to focus on the Loan Portfolio because the other factor, the interest rate, is capped by regulators in some countries, and is not always a parameter which MFIs can freely change.

The loan portfolio can be broken down as follows. The 3 items colored in red are the key indicators on which I would like to elaborate further.

- Productivity (# of disbursed loans / LO): One of the most important factors is Productivity, which here means the number of loans disbursed per loan officer. This indicator shows how many loans a loan officer can handle at a time, or how many new loans a loan officer can disburse in a certain period.

This indicator can be further broken down by branch or product. The productivity is highly correlated with branch vintage, i.e. the productivity tends to be lower at a newly opened branch but it improves as time goes by as officers get trained and become more experienced. Also, this indicator can be further improved through streamlining operations / processes through technology, such as the use of a Digital Field Application, automated underwriting, cashless payments etc.

One example of this at Gojo is a Digital Field Application called Bridge, developed by our tech team, whose MVP succeeded in significantly reducing the registration and loan approval time from 3 days to just 40 minutes! With the device, the loan officers are able to spend more time on client sourcing instead of becoming engaged in unproductive paperwork.

- Loan size: MFIs are willing to offer larger loans to customers who have repaid previous loans, as they can see more of the customer’s credit history than before. But for the MFI to be selected as the customer’s lender of choice, they need to keep a good relationship with customers through close and constant communication, otherwise the customers would end up changing their lenders. The MFI offers larger loans when the MFI is confident enough that the customers will repay the loans.

Therefore, to offer larger loans, it is critical for the MFI to have a deep and up-to-date understanding of customers, including but not limited to, their business, financial situation and personal events. Considering this, although I mentioned the role of technology above, the microfinance industry will not immediately transition to fully tech-equipped services, unlike many other industries, but "tech & touch" will be the key concept for MFIs at least for several years going forward. Given that many MFI customers still do not own smartphones/smart wallets, data about their business situation, financial needs and other life events cannot be collected through these kinds of devices but needs to continue being collected through human touch to some extent. Modelling loan size therefore means we have to take into account the MFI's current and future capacity to collect data on customers and assess their creditworthiness.

- Branch expansion (# of branches): Room for branch expansion largely varies by country. For instance, in some countries such as Bangladesh, financial services have already spread widely to the bottom of the pyramid, but other countries still contain large numbers of underbanked or unbanked people. In more competitive markets, the MFI needs to have some unique selling point or advantages compared to existing players, whereas in less competitive markets they would be able to enter more easily.

The decision on whether to open a branch depends on potential demand for credit, risks, economics, the competitive environment, and many other factors. An additional factor to take into account is the strategy of a MFI, as some MFIs focus more on urban areas while others target rural areas. There are financial institutions which do not have physical branches, rather operating through agent networks. For such institutions, we would possibly use the number of agents instead of the number of branches.

Although obviously there are many more factors to be considered when developing a financial model, such as operating expenses, fundraising and so on, I believe these three items above are the most critical and impactful items to microfinance businesses. At Gojo, we have seven partners as of now and while each partner has a different business model, the key financial success factors for most of them are the three I have outlined above.

Ryo Satake is an accountant and works in Gojo's finance and strategy and analytics teams. He recently led the process of financial modelling for Gojo's overall business and has helped to formalise the budgeting and financial reporting processes for Gojo's partner companies.

Data is the new oil?

In the past decade, the phrase “data is the new oil” has become hugely popular, with hundreds of articles and talks using this metaphor. And there is good reason for this: many see data as the “fuel” which is giving energy to the 21st century economy.

Data on its own has no, or little value - similar to crude oil, it needs refining to become a useful and valuable resource. Only after we process our data, put it into the right context, and use it for decision making, do we get the real benefits (in the same way that oil is much more useful when turned into petrol, asphalt or plastic). To do so, we need infrastructure for collecting, storing and processing the data - which is another similarity with the oil industry.

But is this metaphor really fitting?

First, oil is a finite resource, consumed over time, and rarely reusable. This is very different from the nature of data- data is (almost) unlimited, reusable and multiplies whenever we cross it with other data (we create information, rather than using up data). This gives us unlimited opportunities without having to worry about running out of “fuel”.

Second, with oil you need to start big - the infrastructure is very complex and it requires a huge investment. Again, data is very different - you can start from simple data analytic functions, gradually developing your capabilities and outreach. It is also possible to test solutions and pivot if the chosen path does not fit your business.

Third, you can store crude oil and it will still keep its value, whereas data very often loses its value over time. For example, records of some events age very quickly, and can only bring benefits if used immediately.

Finally, in case of leaks, oil can be cleaned up (although the damage to the environment is done and not always fully reversible), while in case of data it is impossible - leaked/stolen data can damage businesses and people’s lives for many, many years.

(S)oil

While listening to The Data Strategy Show1 podcast, I encountered for the first time the idea of “data as a new soil”. In the episode they mention the soil metaphor in passing, in contrast to oil. I found the soil metaphor to be much more accurate and decided to extend this thinking further.

First of all - you need to work patiently with data/soil to bring value. To grow crops, you need to know the quality of your soil well (explore your data), understand what crops you can expect to grow on this type of land (understand the business context), prepare the soil for agriculture (prepare data), sow seeds (run analytics), water crops and look after them (enrich your data, observe the results, improve analytics), protect from pests (ensure data security), harvest crops (make use of ready information), and… iterate or improve on the process.2

Moreover, the soil metaphor is useful to show that without previous experience it might be better to turn your enterprise into a data-driven one gradually. As with soil or land - if you are new to agriculture, you can start with a small plot, learn, experiment, pivot, and progress with time. Unlike with oil, you don’t need to build the whole operation from day one, but can start small and keep gradually improving.

You also need to be patient - careful preparation, good understanding of data and business context are key to obtaining the best outcome and should not be hurried. Data projects you start now might bring value after a few years - crops you planted today will not grow in a few days.

Of course, the examples above do not exhaust the similarities between data and soil, but they demonstrate the usefulness of the soil metaphor.

In the context of microfinance

In the microfinance context this metaphor is even more appropriate- and it is not only because the low income households we serve very often make a living from agriculture or animal husbandry.

The microfinance sector has not usually been associated with being “data-driven”. Access to data has historically been limited, the need for data analysis has not been recognised, and the lack of proper infrastructure for data was very common. With growing usage of smartphones and tablets, however, the situation has slowly started to change, this change has rapidly accelerated under COVID-19 - more and more microfinance institutions are starting to implement better data collection methods, build (or outsource) data analytics, and use data more often in decision making or product development. But (almost) everyone proceeds in the same way as a farmer starting to cultivate a plot of land - start with a small project, learn, experiment, and then pivot or scale. And just as with growing crops: for some outcomes we will need to wait a little while.

Finally, one important point: data belongs to the people, to our clients. They give us access to their personal information and in exchange we improve our operation, pricing, and product fit. Together, we are cultivating the soil and sharing the fruits of our labor. Sometimes literally.3

Tomasz Ociepka works on data analytics at Gojo. He is currently working on setting up Gojo's data lake for the secure storage and easy analysis of data from Gojo's partner companies.

Last March, I conducted two weeks of ethnographic field research in rural Cambodia with the local staff at our partner company Maxima.

Aside from learning about the villagers and their behaviours around money, I also tried to understand their relationship with technology.

During my research, I observed one phenomenon that surprised me.

Many of the homes I visited had mysterious numbers written on their ceilings. They were written with permanent marker, or etched into the wood. I was baffled by what they were.

Can you guess what they are?

It turns out that they are phone numbers of contacts that are important to them — doctors, police, their family members, and relatives.

The baffling part is that these people all owned feature phones, and some of them even owned smartphones.

So naturally I asked them, “why don’t you put these numbers into your phone?”

Their responses made me smile.

“I don’t know how to register numbers into my phone, I only know how to receive calls”.

“My phone is in English and besides, I can’t read”

“If I lose my phone, I would lose my data.”

“If the numbers stay in the phone, they sometimes get deleted. They never move if they are on the ceiling.”

I felt enlightened after hearing their responses. It became clear to me how their relationships to their mobile devices are quite different from the relationship I have with my smartphone.

For me, this leads to other interesting questions we could ask like…

- What are their relationships with their mobile devices like?

- How would that influence their relationship to mobile apps?

- Does this behaviour tell us anything about the strengths of social ties in these communities?

- Are there clues we can derive from the way people use spatial memory to organize information?

How many people do you know that store phone numbers on their ceilings at home?

Koh designs products and services for Gojo. He spends time listening to clients and potential customers to deliver well-intentioned financial and digital products for low-income households.

Since starting my career, I have worked for a few organizations that practiced diversity in different manners. As I’m in charge of HR at Gojo now, I’ve been working on increasing diversity, drawing on my lessons learned from past experience. In this blog post, I’d like to share my experience so that this might help those interested in joining Gojo or provide food for thought to those interested in promoting diversity at their organizations.

Diverse global firm, homogenous local office

I started my first job at the Tokyo office of a global firm. Despite being a part of an international company, the corporate culture of the Tokyo office was very Japanese back then (2005), due to the fact that Japanese staff accounted for the large majority of employees. I felt a strong pressure to conform to the social norm of the Japanese male-dominated corporate culture, which made me uncomfortable and created unnecessary stress, not only at work, but also at informal gatherings outside the office. As someone with a minority trait, I felt suffocated that I needed to adjust to the behaviors expected by the majority.

Fortunately, this situation changed completely when I got a 1-year assignment in Germany. I was assigned to cross-border projects which had an international team setting. Having team members from multiple countries, there was no need to force myself to adjust to a certain culture. I felt more comfortable, and started to perform better at work.

There was an incident which made me realize the benefit of diversity. When the end of the 1-year assignment was approaching, I started to feel stressed about going back to the Tokyo office. When I was casually lamenting about it, my Turkish and Mexican team members told me, “Why don’t you change your contract to Germany? You enjoy working here, so it makes more sense to stay.”

Before they brought it up, I had never thought about changing my contract as all of my Japanese colleagues were going back to Japan after the 1-year assignment. However, my team, coming from a different background, raised an otherwise very logical point to prioritize what was better for my performance and mental health. I actually managed to change my contract from the Japan office to the Germany office, and ended up staying there for 3 years. It became a turning point of my career. Without this question from my team, my career could have been very different.

From this, I learned that people can perform better in an environment where they don’t need to worry about unnecessary social pressure, and also that diversity brings new perspectives that question one’s common sense.

Intentional inclusivity at an international organization

Prior to Gojo, I worked for IFC (International Finance Corporation), which is part of the World Bank Group. I believe IFC must be one of the top organizations when it comes to embracing diversity. Its staff represent more than 150 nationalities, and work across more than 90 countries. In addition, IFC is owned by 185 member countries, who keep an eye on the organization’s pursuit of diversity as its shareholders.

IFC’s policy on diversity manifests in many HR processes as something similar to “affirmative action”. For example, in recruiting, there is a clear target for diversity. I joined IFC through the Young Professional Program, and out of 10 colleagues who joined IFC at the same year, exactly 50% were women, and 50% came from emerging markets, including 3 from Africa.

Another area in which IFC’s diversity goal can be seen is promotion. There is a certain target to promote gender equality in management, or promote staff from under-represented regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa. To be honest, it can be frustrating at times when you are the one not prioritized by these criteria. However, diversity brought much more benefit than detriment to me, as I felt free to be myself without worrying about social stigma or intolerance. I felt protected as well, supported by many HR policies and welfare programs which were inclusive and available to all who have various family or personal situations.

From IFC, I learned that diversity leads to HR policy and an atmosphere which make not only specific groups, but everyone, feel comfortable at work.

Gojo’s principles on equality

When I was looking for jobs in Japan where I hadn’t worked for 13 years, my biggest fear was whether I could adjust back to Japanese corporate culture. I came to know Gojo for its work in microfinance, the sector I also covered at IFC; however, the biggest reason I chose Gojo was its corporate culture, which is far from the typical Japanese work environment I was afraid of.

What I personally think makes Gojo special as a workplace is its sympathy to minorities and underprivileged people, which is exemplified in Gojo’s mission and values. The CEO himself, Taejun Shin, is a minority and has had his own struggles in life. When I was debating whether to accept the offer to join Gojo, I asked for lunch with Taejun and shared my personal story being a minority. He immediately showed his understanding and made me feel accepted. Based on our own experiences, we share the same view that the more diversified the environment is, the more people can thrive.

When I started at Gojo in mid 2019, diversity was relatively limited, with a mostly Japanese team. Since then, by expanding our recruiting efforts, we have managed to build an international team made up of members from India, Taiwan, Myanmar, China (Uighur), Singapore, Poland, Italy, Germany, France, and beyond.

How Gojo is evolving through diversity

There are many positive changes we have witnessed from the increased diversity. First, new perspectives have been brought on the way we work, from our communication style to work-life balance. For example, Japanese tend to prioritize consensus-driven decision making until reaching the best possible solutions, while Europeans tend to make quick decisions and then improvise along the way. In terms of work-life balance, when Europeans take vacations, they tend to take a week or more off at a time, whereas Asian people tend to take a day or two here and there. We don’t make quick judgements on which way is better, but we learn from each other and reflect on the areas for improvement and change.

Second, diverse cultures are giving us an opportunity to train ourselves to be better at handling cultural differences. In 2020, we certainly faced more cultural conflict than before, due to different backgrounds not only in terms of nationality but also profession (e.g. engineers and management consultants). Having overcome such conflicts, the individuals and also the company as a whole have become better at imagining the other side’s perspective, which is critical for our business, where we always imagine how our clients in the field live their life.

However, Gojo still has a long way to go. Japanese nationality still accounts for about 50% of our holdco members. The management and board of directors are all men, except for our newest board member, Royanne Doi. And needless to say, diversity goes way beyond nationality and gender, to cover various aspects of one’s background.

I believe that diversity will question the status quo and promote innovation, which is necessary to achieve our aspirational mission to extend financial inclusion to 100 million clients. As the person responsible for Gojo’s HR, I'd like to contribute to creating a workplace where everyone feels comfortable and passionate about pursuing the best version of themselves.

Takao Takahashi leads Corporate Planning, strategy setting, and HR at Gojo. Prior to Gojo, he spent 7 years at IFC as an Investment Officer, and was previously a Prime Minister's Fellow in Bhutan.

Myanmar’s financial services industry is nascent compared to the rest of the world, since the country only started to open up after the transition in 2011 from military rule to a civilian government. With the transition came liberalization of the financial services industry, with the Central Bank of Myanmar becoming an autonomous entity, and the enactment of the Microfinance business law in 2012. Since then, the industry has been playing catch up with the rest of the world, specifically in the area of mass market consumer lending.

Banks in Myanmar have traditionally served the corporate sector with credit, and have only recently started to slowly expand their reach into the SME sector, with a couple of non-traditional banks dipping their toes into consumer lending. The biggest obstacle banks face is the majority of the population’s lack of credit history. This creates a catch-22 for the risk-averse banking sector, who will not lend to consumers without credit history, but cannot build credit histories for consumers without taking the risk of lending in the first place. Microfinance institutions have been left to pick up where banks fell short in providing lending services to consumers, taking high risk, and building credit histories.

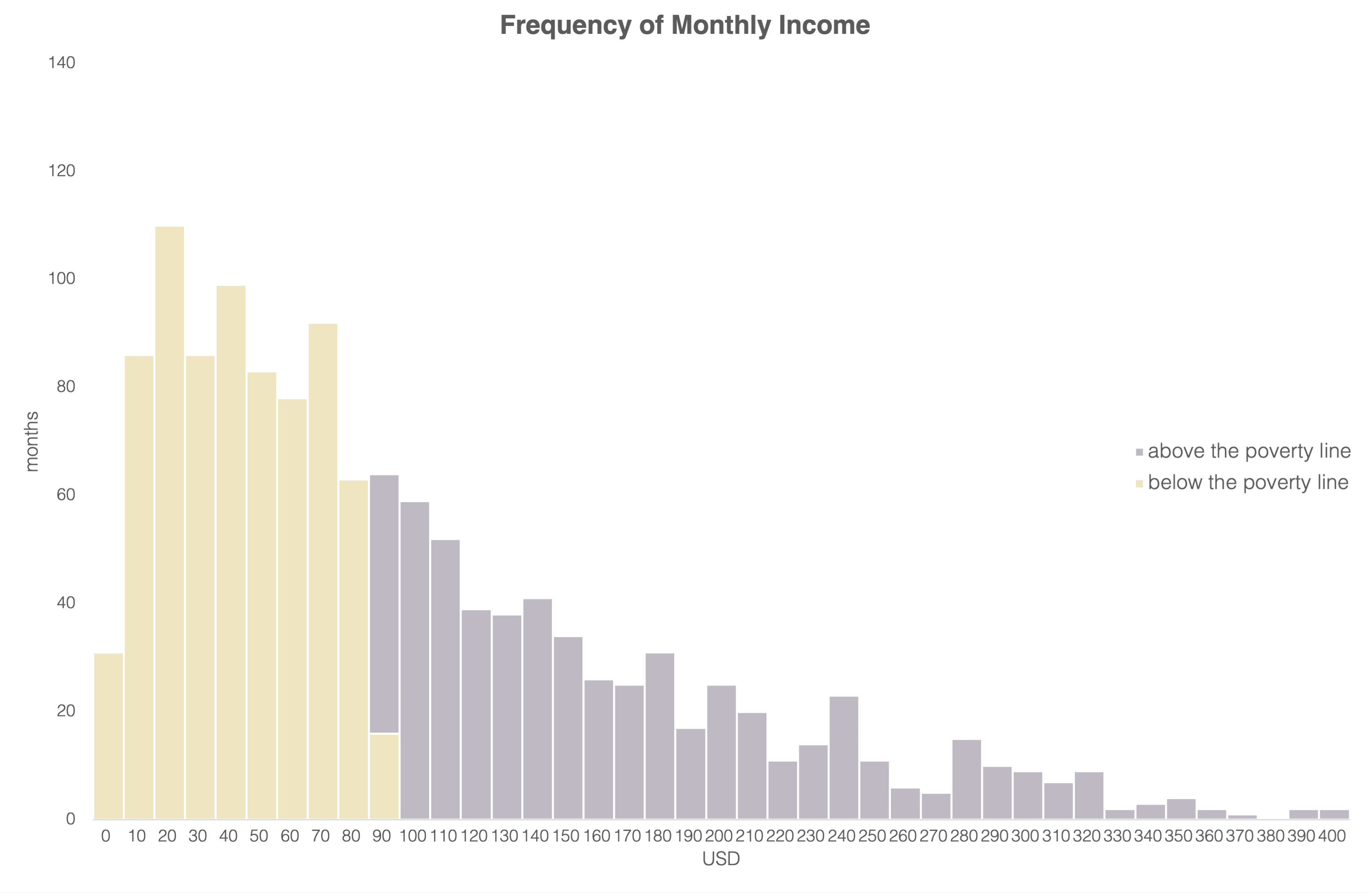

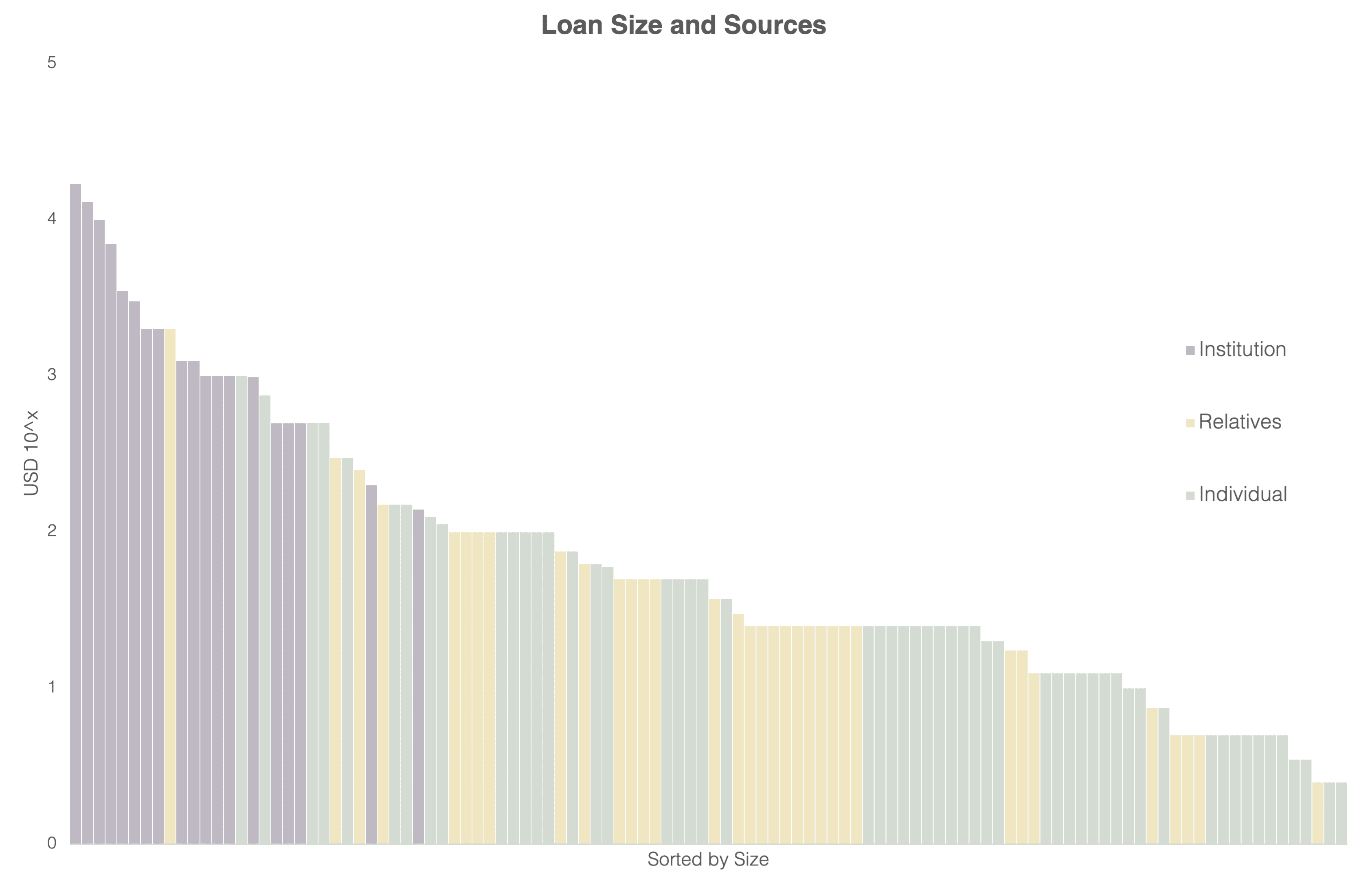

Microfinance in Myanmar started with the mission of getting people out of poverty and extending financial inclusion. The gap in the provision of mainstream financial services has led to the popularity of microfinance among the un/underserved credit-hungry populace. As a result, while maintaining its social mission, the microfinance sector has also grown to be a provider of mass market retail lending, ranging from consumer lending to micro/small business lending. Such rapid expansion in the lending scene has brought the need for credit scoring to the forefront, especially among the no/thin file segment of the population. This is where the sector’s years of trial and error in building the credit history of no/thin file clients can begin to bear fruit, as the sector starts to address the need for stronger credit scoring and risk management by building credit scorecards.

Credit scorecards: An introduction

So, what is a credit scorecard?

It is the heart of credit scoring. It is a checklist of data points that are collected and weighted to spit out a score that we call a credit score, and financial institutions use this score to measure the risk level of a consumer. Consumers who have high credit scores are usually considered low-risk, while consumers on the other end of the spectrum, who have low credit scores, are considered high-risk.

The credit score and its associated risk level can decide whether a consumer gets approved for a loan, the pricing on the loan (risk-weighted pricing), and in some cases, even the loan amount and term. With credit scoring playing an important role in the decision-making process, the need to understand how the credit scorecard is made becomes critical.

A credit scorecard is created by looking at data on past loans that the institution has made so that it can extrapolate its experience of past loans to future consumers. To do this, they first need to classify consumers as either “good” or “bad”, and an analysis is carried out to explore and extract a set of characteristics that makes a borrower “good” or “bad”. In this scenario, the definition of a “bad” consumer, in hindsight, is any consumer to whom the institution would choose not to offer a loan again. There are two main types of scorecards for making such an analysis: an expert scorecard and a statistical scorecard.

Let us begin with the expert scorecard. It is the most basic credit scorecard and the most commonly used scorecard. As its name suggests, it is a scorecard made with inputs from an expert. People with years of experience in lending and credit appraisal make a list of characteristics to check and score for any consumers applying for the loan. This is a very manual process that relies on the personal experience of seasoned loan officers and credit managers in the case of microfinance, and of the underwriting team, in the case of banks.

The statistical scorecard does not draw on any personal experience but instead on statistics. The scorecard is built by using regression analysis to find correlations between data points collected from consumers and the performance of their past loans. This often means that an institution has collected hundreds, if not thousands, of data points from consumers and their past loans to find the correlations.

There is a midway approach, aptly called a hybrid scorecard. This is the combination of the two scorecards where the statistical scorecard is evaluated by experts to create a final version of the scorecard.

Creating a credit scorecard

Financial institutions that are looking to build a scorecard need to evaluate whether they have sufficient data points covering:

- Transaction history (volume and amounts of deposits, withdrawals, cash ins, cash outs, and payments)

- Saving history (balances in individual account or across all deposit accounts)

- Demographics (age, gender, location, etc.)

- Loan performance (number of times a consumer is late for previous loan instalments, number of days late for previous instalments, history of delinquency)

- Income data (individual / consolidated debt to income ratio)

- Relationship with the institution (how long the consumer has been with the institution, other products of the institution used by the consumer)

- Alternative sources of data such as the credit bureau, call/text data, social media usage, etc.

The more data points, the better the statistical scorecard is. If the institution does not have access to or has not accumulated sufficient relevant data points, they can create an initial scorecard by using expert team members who have the experience to make judgement calls in lending, while gradually transitioning towards a statistical scorecard.

Transitioning to a statistical scorecard: The example of MIFIDA

The following is an example of one of Gojo’s partner companies, Microfinance Delta International (MIFIDA), and its journey to create a scorecard.

MIFIDA is a microfinance institution in Myanmar with around 150,000 customers and a portfolio of around $40 million. It was incorporated in 2013 but hit its stride in 2017, when it grew from a handful of branches to 60+ branches today. With such growth, the need to reevaluate its risk management policies and credit assessment became apparent. This in turn highlighted the need for a scorecard for its customers.

MIFIDA already had a scorecard for its MSME customers, but it was a basic expert scorecard that covered the usual characteristics such as: debt coverage ratio, the ratio of repayment amount to income, number of outstanding loans, age, years in the business receiving the loan, etc. But it did not have a scorecard for its mass market lending products, such as its group loans.

MIFIDA therefore set out to reevaluate its current MSME scorecard and to create a new scorecard from scratch for its group loans. Below, I will cover the re-evaluation and update of the MSME scorecard, and the challenges we encountered in the process. I hope to cover our journey toward creating a new scorecard for the group loans in a later post.

Relevant data is paramount for making a statistical scorecard, and this is exactly what MIFIDA did not have. It had only implemented its core banking system in recent months and even then, it only had transactional data going back as far as the data that had been migrated into the system. Despite being around seven years old, MIFIDA did not have digitised historical data on clients. There was also no guarantee that the digitised data was reliable.

This ruled out immediate creation of the statistical scorecard for MIFIDA, but as they had experts who have been making loan decisions for years now, they decided to create an expert scorecard based on the experience of their staff. They listed down everything that made a consumer “good” and “bad”. From that listing, the team trimmed it down to 14 specific characteristics that would be most telling of the customer’s behavior and provided the weightings on each characteristic to be scored. A new application form was then drafted so that the data needed for scoring could be captured.

Market-wide challenges in credit scoring

MIFIDA is using this new expert scorecard and application form as stepping stones toward a future statistical scorecard of its own. Apart from the lack of data points mentioned above, the current challenges that MIFIDA is facing in creating the statistical scorecard are:

- A lack of data analysts and data scientists in Myanmar. Even if you have the data, there are few people in Myanmar with the skills to do the necessary analytics to build and produce the scorecard. It would require a person well versed in R or Python to handle large datasets, do exploratory data analysis, find correlations using regression or one of a few other methods, and then make a production-level scorecard that could be used in the field.

- The lack of a credit bureau. Anyone who wants to double check a customer’s self-reported credit history will simply have to trust the consumer as there is no centralized database to check against. In recent years, MCIX (Myanmar Credit Info Exchange) has started to provide such a service to the microfinance sector, but it is still a nascent endeavour, as it currently only shows some of the loans that the customer has taken from other microfinance institutions, and sharing of delinquency data is still a work in progress. Until MCIX or the national credit bureau are fully-fledged, with the majority of financial institutions onboard, MIFIDA will have to check credit histories either by building these histories itself, or through traditional means such as asking family, relatives or local authorities.

- Tying into the institutional lack of data is that most customers are no/thin file customers who are only just beginning to be financially included. This means that they are at the start of their journey to build a credit history with a formal financial institution. Building such histories takes time. On the other hand, it also presents an opportunity to financial service providers to get the data they want to collect from customers right, so that it can be processed and used for scoring in the future.

Financial institutions in Myanmar, MIFIDA included, are currently working on overcoming those challenges of building a statistical scorecard and transitioning from expert scorecards, as there is a whole world of new opportunities if the transition is successful.

The rewards of better credit scoring

Myanmar has seen one example of an institution that is inching closer to a full statistical scorecard, and the opportunity this has provided to that institution.

The institution is Yoma Bank. Their digital lending product, called SMART Credit, is made for the mass market with a hybrid scorecard in the backend that is recalibrated every year with the help of Experian, one of the biggest providers of credit scoring and analytics in the world. This has helped Yoma Bank to expand its lending portfolio to everyday consumers and to a new market segment that it would not normally lend to due to the associated risk.

MIFIDA hopes to replicate that success by building its own customers’ credit history, while using an expert scorecard to mitigate the current risks until sufficient data is collected for a statistical scorecard. MIFIDA will also look to move onto digital lending and digitizing much of its operations so that its loan officers can focus more on building relationships with customers instead of focusing on application forms and transactions. Such digitization would allow for the collection of well-structured data points that could be used to move onto a statistical model, enabling MIFIDA to expand more easily to new customer segments with reduced risk in future by providing a comparable baseline for the new segment’s credit scoring.

Kaung Set Lin is Gojo's Country Officer for Myanmar, and has over 6 years of experience in Myanmar's financial sector, primarily focusing on developing and implementing digital financial products. His work includes managing the rollout of Gojo's digital products, including our Digital Field Application (DFA).

In February, I joined Gojo as CTO to use technology to support and accelerate our mission to extend financial inclusion to everyone. In this blog post, I would like to share one of the key pillars of our technology strategy: developing digital financial infrastructure for the less privileged.

We are all well aware that there is a well designed financial system and infrastructure which enables us to transact money safely and securely.

Financial infrastructure plays a critical role in any country’s economic and societal development. Today’s long evolved financial infrastructure (which includes central banks, banking systems, payment networks, and identity or credit scoring agencies) has perfected services for the most common use cases.

We may take its robustness and efficiency (or sometimes inefficiency) for granted in our daily financial interactions, for example:

- You can easily get a new bank account with a preferential interest rate in return for parking your money. Granted, if you are not used to digital banking, then it’s a bit of a hassle. But if you are used to it, then opening a bank account only takes a few clicks on your smartphone.

- Your monthly salary arrives instantly to your bank account and you are notified.

- You can get immediate credit if you face a sudden liquidity problem. You can even shop around different banks/fintechs to get a favourable lending agreement.

- You can use your credit/debit card when you shop and avoid having to carry cash. You can even use Apple/Google/Samsung Pay or a QR code if you wish.

- If you happen to need cash, you can walk to a nearby ATM and use your debit card to withdraw money from your account.

- You can send money to your friends or loved ones in a few clicks from your browser or mobile app and the recipient gets it as quickly as a text message (though of course, for cross-border transactions it's not quite that fast).

All the above daily scenarios are made possible by a financial infrastructure made up of at least one or more entities. In short, a financial infrastructure enables money to move throughout an economy, functioning as a platform for transactions, whether these are payments, financing, or the transfer of bonds and stocks.

The strength and weakness of our present financial infrastructure is its over-reliance on the customer's ability to open an account in a regulated financial institution, such as a bank or non-banking financial institution or a regulated fintech.Unfortunately, this excludes a significant minority and represents a major hurdle for a lot of people who could otherwise benefit from accessing the financial infrastructure. Many organizations in the world focus on bringing this un/underserved population to the formal financial system but have not met with great success.

In some of the countries where we work, governments have recently taken concrete steps to improve the digital financial infrastructure and have brought a lot of people into the formal system as a result. In these countries, we leverage the infrastructure or work with them. But in the vast majority of places where we operate, we still face this problem where many are excluded from the infrastructure of the formal financial system.

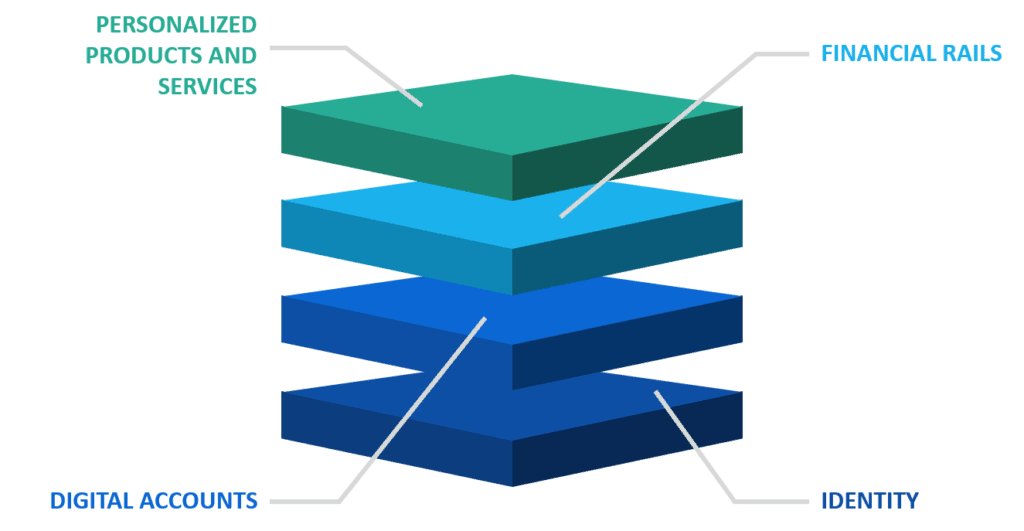

At Gojo, we are on a mission. We believe that everyone in this world should have an equal opportunity to access quality financial services. Gojo’s Tech team is using technology to solve these critical problems for financial inclusion. So we have started to develop our own digital financial infrastructure. Our digital financial infrastructure consists of a few key building blocks, as given below:

1. Identity

This is the foundation for everything. In order to serve our customers, we have to establish their identity and our level of confidence in their capacity to use the financial service they are requesting.

Traditionally this has been done using a formal process of KYC (Know Your Customer) by submitting government issued verifiable identification, such as a national identity or voters card or shop ownership license. The next step would be the analysis of a customer’s past financial transactions to understand their creditworthiness. Traditionally financial institutions use credit bureaus to evaluate their customers’ liabilities and financial standing.

But in our case, customers seldom come with any verifiable, government issued ID. Moreover, they have zero traces of past financial transactions with which we might assess their financial status. Instead of rejecting these customers, we are planning to use machine learning algorithms to identify and assess our level of confidence in clients for each financial service. We have started putting together our big data infrastructure and plan to integrate multiple alternate data sources such as mobile network operators (for billing, data, and call details), leading ecommerce platforms for past transactions, and behavioural analysis such as psychometric evaluations.

In addition, there are many organizations working to onboard and provide a verifiable digital identity. We would like to join together with organizations such as ID4D or other ID as a service (IDaaS) providers to provide a secure digital ID to our customers.

2. Digital Accounts

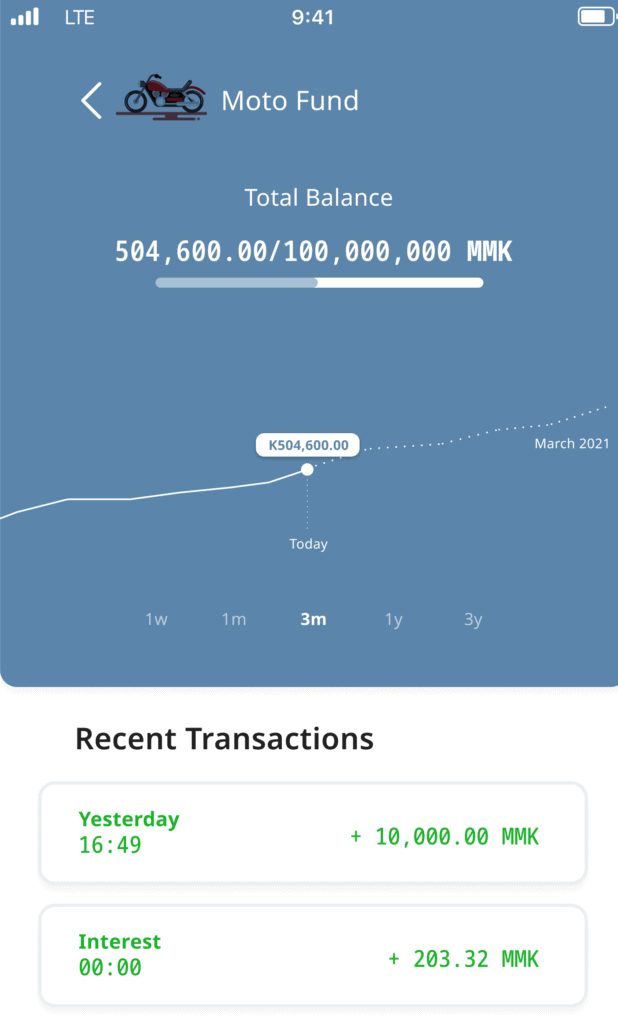

Once we provide or recognize a customer’s unique ID, we can begin to offer financial services. But here we plan to follow a fully digital/paperless approach. We are in the process of developing our own mobile application for customers. This is a logical step since a considerable percentage of our target population uses mobile internet and smartphones. For example, as of January 2020 in Myanmar, there were approximately 68 million mobile connections and internet penetration stood at 41%4.

So if a customer wants to request a loan or deposit some money for their savings, they will be able to access their digital accounts through the mobile app and see real-time updates of their activities, such as daily interest accruing from a loan, their financial goals, and more.

In order to offer digital accounts to customers, we need sophisticated backend infrastructure such as a cloud-based core banking system and its associated tools. We are currently investing heavily in building our common digital platform in the public cloud to achieve scalability and growth.

3. Financial rails

The next building block in our digital financial infrastructure is financial rails. There should be a simple and transparent mechanism to move money to wherever the customer wants. The most common scenarios are payments, P2P (person to person) money transfers, and remittances. We are partnering with local real-time payment schemes where available, such as UPI in India, or leading payment schemes and alternate real-time payment services such as Mojaloop5. Mojaloop is an exciting project and we are already in the experimentation stage with it.

4. Personalised products and services

We believe in data-backed product creation and know that there will not be one single product that works for all customers. We will use data to identify customer pain points and introduce products to address them. All of our new product development goes through a human-centered design process where we ensure that the product we are putting in the market is genuinely useful for our customers. We carry out constant experimentation and prototyping to identify what makes our customers happy. This constant experimentation requires a lean and agile culture with flexible technology capabilities. At Gojo, we are putting each of these building blocks in place one by one.

We will be deploying our digital financial infrastructure stack in countries such as Myanmar and Cambodia. We hope that as a result, our customers will be able to get an account without any of the usual hassle, start saving daily, withdraw money whenever they want, apply for and obtain credit within minutes, and transact confidently through their digital wallet - and all of this will be possible without needing to register for a bank account.

Syam Nair is Gojo's Chief Technology Officer. He joined in February 2020, having previously worked for Visa and Mastercard. He leads the development of Gojo's technology strategy.

From 2016 until recently, I was fortunate enough to meet many investors for Gojo’s equity financing rounds from Series A to D.

This blog post aims to share a few painful moments when I received candid feedback from potential investors. I now see these pieces of feedback as a gift, and hope that the following three gifts I received can help those looking to raise funds, especially for startups. All three are true stories.

1. “You are like a messenger boy.”

I will never forget this message and genuinely appreciate him giving me such straight forward feedback. This message in the very early days of my fundraising journey helped me a lot.

At that time, we were about to close a deal with one of the best-known VCs in Japan. The VC was not a lead investor. Given VC financing practices in Japan, follower investors do not have much room to negotiate a share subscription agreement's terms and conditions.

The venture capitalist understood the limitations and conceded on most terms while requesting a few minor points where he could not compromise. As the person in charge of negotiating with the VC, I consulted our legal counsel, and we decided to push back on his request.

He accepted our comments, but at the end of the conversation, he told me, "I understand your attorney is doing a great job, and I can understand his points. But I haven't heard your views on my request in your own words. Please explain why you think your company should not accept our offer. You are now representing your company in front of me. We are now turning the final corner of this deal because I believe in your team and you. Give me your own words instead of a lawyer's textbook answers. "

I could not answer well because I had relied only on the legal counsel's comments and had not thought deeply about it myself. Then he told me,"You are like a messenger boy. I say sorry, but messenger boy has no value to me."

My takeaways:

- Speak with my own words, not borrowing from others, even if it is about a technical matter.

- During negotiations, I represent the current shareholders in front of a future shareholder. I need to give confidence to my counterpart, who will become a shareholder soon after this negotiation.

2. “See you again someday after you study us.”

Over our Series B financing period in 2017, we looked for a strategic investor who could create business synergies with us, rather than only injecting capital. Very luckily, we got the chance to meet with a top executive of a multi-billion dollar company, which sells consumer products globally. As usual, we prepared by studying their website, his book, and past newspaper articles before meeting him at their office.

At the executive’s office in a Tokyo skyscraper, we discussed the potential for business synergies after a brief corporate presentation. Our idea was to collect market data through our multi-national microfinance business network, which the company or market research firms would not usually be able to obtain because we targeted only low-income mothers in rural areas. They would become the company's future main client segment. We confidently said to him, "Why don't you obtain data from our company to track the consumer trends while collaborating with us? That could be a unique selling point for your marketing. Since we work in developing markets, we could bring you the contextualised data if you were to become our strategic investor."

He answered, "Oh, that sounds like a good idea. Could you let me know what feedback you’ve heard from clients on our product in these countries? Or could you share some personal spending data you’ve collected so far about our product segment? I'm sure you must have studied several samples before coming to me."

Unfortunately, we could not answer because we hadn’t researched the issue sufficiently before our first meeting. He seemed confused by our poor preparations. He said, "See you again someday after you study us."

Needless to say, the meeting ended 30 minutes earlier than scheduled, and the deal didn't happen. Instead, we wrote a letter apologizing for taking up his precious time.

My takeaway:

- Lack of preparation means a lack of effort. We should be as prepared as possible so that we can inspire investors.

3. “I understand your vision, however, you look like a swindler to me.”

By November 2016, two years and four months had passed since Gojo's inception. We were sourcing Series A investors, targeting mainly individual angels. The minimum ticket size for angel investors was 10 million JPY, approximately USD 90K at that time. At just two years and four months, our company didn't have a brilliant track record. However, we had to offer a reasonably high valuation to preserve our founders' ownership and avoid the mission drift seen in the microfinance sector in the early 2010s.

In many cases, for start up financing, personal introductions are the most powerful way to expand your pool of investors. The key is to create a network of supporters to get these connections. I contacted many old friends and acquaintances and made many pitches.

I met a 60 year old veteran executive of a company which he had run for 25 years with stable growth. He welcomed me, and we had a casual catch-up, then I made a presentation to ask him whether he could consider an angel investment in our company.

He questioned our top line, bottom line, top-line growth rate, and valuation. Right now, our current valuation comes from a combination of our past track record and future expectations. At that time, our valuation mainly relied on a dreamy goal: our future expectations.

He told me, "I believe that a business should be valued based on past performance, and if there is no track record, it should be a reasonable price. Come to me again when you achieve numbers that can justify your valuation. I understand your vision and passion, however, you look like a swindler for now."

My takeaway:

- While it may be pretty obvious, not everybody can value our beliefs and thoughts as we do. There is no one pricing for start up financing. Try tapping a number of investors until we find those who can understand the value of our offering.

In conclusion

Painful feedback is food for better performance. Our ability to accept it honestly depends on our determination to achieve the vision. As long as we are determined to achieve our vision, we can happily receive this feedback as a gift even though emotionally it’s not easy.

There are so many hard things in the fundraising process that we can not imagine just from reading success stories in outlets like TechCrunch.

Adding shareholders to the cap table is similar to marriage. I hope those who read this blog post can overcome hard things and find the best partner to change the world with you!

Postscript

The investor who told me I was like a messenger boy founded his own venture capital firm after spending two years as a shareholder of Gojo. After his first investment in Gojo, he connected us with his own networks of investors built throughout his career, and we can attribute around 25 million USD of funds successfully raised to his introductions. He also invested in Gojo again from his new venture capital firm. Fast learning can attract additional investment and strong support from investors. As our CFO Kohei says in his recent blog post, fast learning creates credit with investors. Credit translates into the capital to change the world.

Natsuki Sugai has worked at Gojo since 2015. In that time, he has worked as a country representative for Myanmar and has led Gojo's fundraising efforts from Series A to C. He currently works on the Operations team, where he develops and refines Gojo's governance processes.

From March to April this year, amid the Covid-19 turmoil, Gojo & Company successfully raised JPY 2.3 billion yen (US$ 22mn) from existing stakeholders and secured enough excess funds to deal with the crisis. The reason we were able to do this is, in my view, was our diligence in communicating both the good and bad news about our management situation to our shareholders.

Looking back on the past, this full-disclosure principle is similar to the way I thought about investor relations at LIFENET, the insurtech company, where I served as CFO while it was still a start-up. The life insurer was forced to face a global financial crisis soon after it commenced operations in May 2008. I still vividly remember the days and nights visiting shareholders and communicating closely with them one by one to let them know how things were going. In those days, I was running around so much that my leather shoes were torn to shreds within six months.

In his recent book Trailblazer, Marc Benioff, the founder and CEO of Salesforce, emphasizes the importance of trust, saying, “Success is built on trust. Trust starts with transparency.” This motto also appears at the top of their community website. My personal belief resonates with this simple statement. When a company is in its early stages, nothing helps to secure the continuous support of stakeholders like transparency.

Gojo & Company, through its affiliated companies, provides financial access to those who are excluded from traditional financial systems. Although the majority of our current revenue comes from microcredit, which is the extension of microloans to impoverished borrowers who typically cannot provide collateral, most of our clients lack sufficient verifiable credit history.

In a sophisticated financial system, when people buy homes with mortgages, purchase goods using credit cards, or when companies borrow from banks, these transactions rely heavily on credit, which is a measure of how well you have done in the past (be it in terms of income, sales, or repayment history). In other words, credit reflects your past. The word "credit" also refers to historical achievements, such as a unit of an educational course you successfully completed, or a list of people who helped to make a film.

In contrast, trust is predominantly about your future, or something which others believe you will deliver. We can think of credit as a more objective evaluation based on past performance, and trust as a more subjective evaluation based on expectations for the future.

In this sense, microcredit starts with trust, building on all the data points we collect to assess creditworthiness. Trust within the community; trust among a group of people who come together to obtain loans; and trust between the loan officers of Gojo group companies and borrowers.

Gojo & Company is paying forward the trust which we received and will continue to build with our stakeholders by extending trust to our clients and building our credit together with them. As our clients build their credit history, so does Gojo build credit with our own stakeholders. I’m proud to be part of this ecosystem, and feel the responsibility to secure continued trust from our stakeholders, so as to contribute to extending financial access and making Gojo’s vision a reality.

Kohei Katada is Gojo's CFO. He leads Gojo's fundraising, finance and admin teams. Prior to joining Gojo, Kohei served as the Senior Vice President of Finance at SmartNews and as CFO at LIFENET INSURANCE COMPANY.

I'd always thought I'd had a poor childhood. But it wasn’t until I lived and worked in East Africa, India, and Sri Lanka for years that I learnt the true meaning of poverty.

When I first landed in Kenya, I was like any passionate young professional aspiring to create impact for the local poor people. I visited slums and rural areas where I saw muddy roads, kids with dirty clothes, trash everywhere, terrible public toilets. I thought to myself: "This is what poverty looks like".

If my journey of understanding poverty had ended there, it's very likely I'd have come up with solutions such as building a clean public toilet, donating good quality second-hand clothes, or hosting neighbourhood cleaning events to pick up trash, etc - all these things we often see or hear about. These are all nice solutions to temporarily treat pain, but very rarely have they worked for poor people and changed their situation permanently.

Why is that?

Because all these - muddy roads, dirty clothes, terrible toilets - are not what poverty is about.

1. Poverty means: Lack of quality options

The first time I met David (not his real name) was in 2016. He sang in a band at night, but what actually paid his living was picking up garbage in slums and reselling electronic parts. He grew up in a slum with his sister, raised by a single mum. When he was eight and his sister was twelve, they were kicked out by their mum. She told them, "You guys are grown ups now. You need to make a living on your own."

That was the beginning of his criminal teenage years.

The options he had were very limited: 1) Starve and try to find some leftover food in trash bins, or; 2) Transport a small bag of "flour" and get some pennies to fill his stomach. (Nobody suspects a kid with a small bag walking down the street.) As a result, he did both.

I tried to imagine what I’d do, if the same thing happened to me. I would have had many good options- I could have gone to my aunt, to the police,or to a teacher. In fact, I think before doing anything on my own, society would have noticed me and offered to help.

Not one of these options was available to my friend David. And that's what poverty actually means: a lack of quality options. A mother who lives in poverty is not deliberately making a choice to dress her kid in dirty clothes rather than clean second-hand clothes; she is choosing between providing clean clothes and getting food on the table. Most of the time, people do not have real choices.

2. Poverty means: Extremely low value of time

We often hear the phrase "Time is money". When you are poor, you have to spend a lot of time just to get a little bit of money. According to a report, Nairobi ranks as the world's 4th most congested city. This is attributed to the lack of a scheduled public transport system and an underdeveloped non-motorized transport network--again, contributing to a lack of quality choices.

Most people who live in slums work outside the slums. They go to nice neighbourhoods to work as maids, guards, construction labourers, and so on. Travel can take up to 2-3 hours each way. That is 4-6 hours every day, just gone, sitting in a matatu (a share taxi). And for safety’s sake, there is absolutely nothing you can do in a matatu, not even using your smartphone.

Transportation is just one example. The effects of this low value of time pervade every aspect of daily life. Everything takes so much more time for a poor person than for a middle-class person. And the less time you have to earn and learn, the less valuable your time will be. It's a poverty trap.

3. Poverty depends on context

When I learnt that poverty actually means 1) lack of quality choices and 2) extremely low value of time, my perception of so-called "poor neighbourhoods" started to change.

In India, I visited some communities in Himalayan regions which have very basic infrastructure, lacking even mobile phone signal. Their clothes are not clean and shiny; they still use traditional toilets; and their incomes are generally low and unstable. However, their neighbourhoods and environment provide an abundance of quality options for water, food, and entertainment, and they have plenty of time for themselves!

Just by looking at the numbers, they may be classified as households in poverty. But in my view, they simply have a different reality of life from those of us who live in developed countries. In our context, their standard of living would be considered poverty; in their context, it's just a normal neighbourhood. And if we force changes on their neighbourhood simply because we judge that they are in poverty based on some numbers on a page, the damage could be catastrophic.

This might be a reason why so many social innovation ideas have failed or even created greater harm than positive impact. Poverty depends on one’s context. Forcing one's expectations onto someone else’s context can lead to disastrous outcomes.

As Gojo works on extending financial inclusion to everyone, we need to understand what poverty and lack of financial inclusion mean to our clients. We must always try our best to listen first to understand and respect our clients' context and to create a solution which truly works for them.

Yung Han Chang works on Corporate Planning and Investor Relations at Gojo, drawing on her prior experience in Sri Lanka as a country rep for Gojo and in Kenya at the Amani Institute, where she completed a post-graduate certificate in Social Innovation Management. She is currently working on Gojo's long-term strategy and governance processes.

Sign up to receive news from Gojo here.